Globalization 2.0: Why the World Is Choosing Security Over Speed

Original Article By SemiVision Research

Introduction — The Structural Turn in the Global Economy

If we had to summarize today’s global economy in one sentence:

We are moving from an era of “making things as cheaply as possible” to an era of “making sure things can always be made.”

This shift is deeper than a recession, inflation cycle, or temporary geopolitical tension. It represents a structural reconfiguration of how the global production system operates — a turning point comparable to the post–Cold War globalization wave of the 1990s.

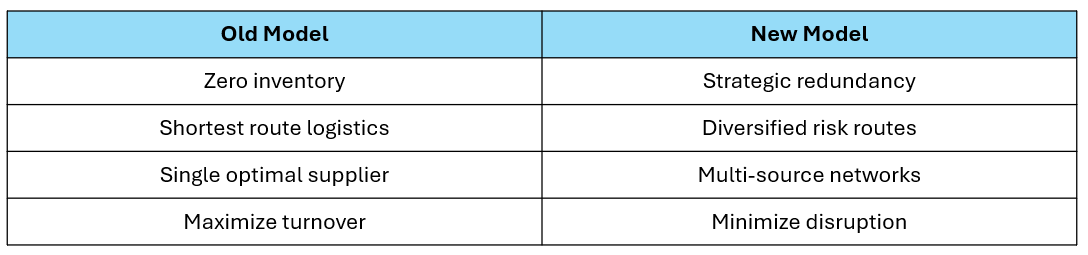

For over three decades, the world economy was built on a singular organizing principle: efficiency. Corporations optimized supply chains across borders to minimize cost, maximize scale, and accelerate capital turnover. Manufacturing migrated to where labor was cheapest, resources most accessible, and regulations most accommodating. Just-in-Time (JIT) logistics reduced inventories to near zero. The result was a system that delivered low prices, controlled inflation, and unprecedented corporate profitability.

But the same structure that maximized efficiency also minimized tolerance for disruption.

A series of shocks exposed this fragility:

The U.S.–China trade conflict revealed how deeply technology supply chains were intertwined with geopolitics.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how a single node failure could paralyze entire industries.

Logistics disruptions — from port congestion to canal blockages — showed that physical trade routes were systemic vulnerabilities.

The war in Ukraine highlighted how energy and raw materials could become geopolitical weapons.

Rising tensions over advanced semiconductors and critical minerals revealed that upstream dependencies could determine downstream industrial power.

These events did not merely interrupt globalization — they changed the objective function of global production.

Where firms once asked, “Where is it cheapest?” they now ask, “Where is it secure enough?”

Where governments once prioritized growth through trade integration, they now prioritize resilience, strategic autonomy, and supply chain control.

This marks the transition from the Age of Efficiency to the Age of Security.

Globalization is not ending — but it is being redesigned. The new system does not eliminate cross-border production; instead, it layers it with political boundaries, strategic redundancies, and risk buffers. Supply chains are becoming more regional, more duplicated, and more state-influenced.

In short, the world economy is no longer optimized solely for speed and cost.

It is being rebuilt to withstand shocks, geopolitical rivalry, and systemic uncertainty.

And that transformation — not short-term cycles — will define global trade, industrial strategy, and corporate decision-making for the next decade.

1. The Peak of the Old Order: How Successful Globalization Was

Post-1990 globalization was one of the most efficient economic systems in human history.

The WTO system, free trade agreements, and multinational corporate networks created a highly optimized structure of comparative advantage specialization.

The guiding principle of that era was simple:

Cost optimization above all else.

Corporate decision logic was straightforward:

Labor cheaper → move there

Land cheaper → move there

Taxes lower → move there

Regulations looser → move there

The result was extraordinary:

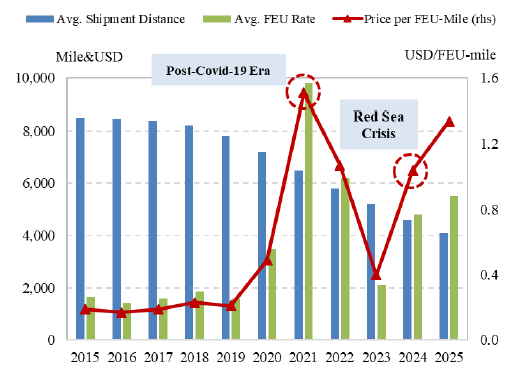

Trade as a share of global GDP surged, production costs fell, inflation was suppressed, and capital turnover efficiency improved. Companies pushed Just-in-Time (JIT) production to the extreme, minimizing inventory and turning supply chains into high-speed global arteries.

But this system carried a hidden vulnerability:

The higher the efficiency, the lower the tolerance for disruption.

2. The Cost Emerges: Globalization Had Political Consequences

The downside of globalization was not technological — it was social and political.

Manufacturing employment shrank in the U.S., middle-class wages stagnated, social mobility slowed, and economic anxiety accumulated. According to the report, this structural dissatisfaction eventually translated into political pressure, forcing policymakers to shift priorities from efficiency to security and resilience.

This marks a historic turning point:

Economic logic is now subordinated to national security logic.

3. JIT Ends, JIC Begins: Companies Are Now Paying for Uncertainty

Pandemics, wars, canal blockages, and trade wars taught firms a new lesson:

The cost of stockouts is greater than the cost of inventory.

The report notes a shift from JIT to Just-in-Case (JIC) strategies, with firms holding 2–3 months of key components.

This is not an operational tweak — it’s a systemic change:

The global production system is effectively installing “airbags.”

But airbags have costs:

Capital tied up in inventory

Higher logistics expenses

Lower overall efficiency

Research cited in the report suggests trade fragmentation will reduce long-term global GDP. This is not collapse — it’s structural deceleration.

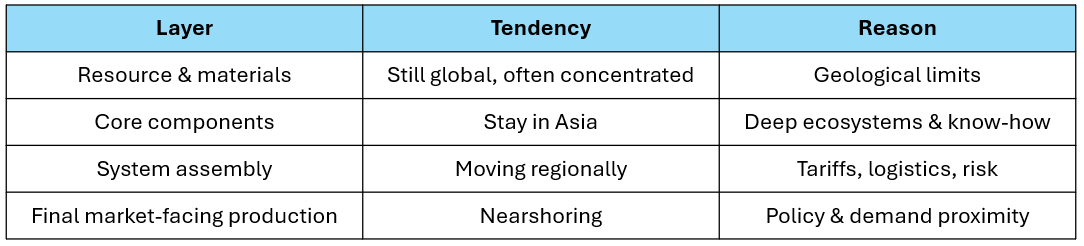

4. Regionalization Is Not Reshoring — It’s Supply Chain Layering

“De-globalization” does not mean a wholesale return of factories to the U.S. or Europe.

What is happening is far more nuanced:

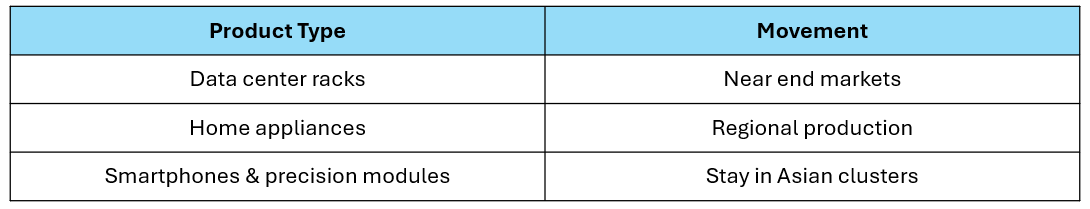

Supply chains are being reorganized by functional layer, not by geography alone.

Instead of one long, efficiency-optimized global chain, we are seeing a multi-layered structure emerge:

This creates a world where production is geographically split by complexity and substitutability.

Let’s examine the major industries.

Textiles & Apparel — The First Movers of Regionalization

This is the most price-sensitive manufacturing segment.

Margins: ~8–15%

Labor cost share: very high

Technology intensity: low–medium

As wages in China rose and trade barriers increased, production shifted to:

Vietnam (trade agreement advantages)

Indonesia (large labor base)

India (scale + policy incentives)

Bangladesh (cost competitiveness)

Gradually Latin America for U.S.-bound supply

But this shift is not just about wages anymore. It reflects three forces:

Tariff arbitrage — firms position assembly inside trade zones.

Lead-time compression — fast fashion demands shorter cycles.

Risk diversification — companies no longer rely on one mega-base.

This industry demonstrates the “outer layer” of supply chain migration:

low-tech, high-labor activities move first.

Electronic Components — Where Regionalization Hits Structural Limits

This is where many policymakers underestimate complexity.

Electronic components (PCBs, passive components, connectors, sensors, modules) depend on:

Dense supplier clusters

Frequent engineering coordination

Real-time process feedback

Shared tooling and tacit knowledge

The report stresses that even when final assembly moves, midstream component ecosystems remain anchored in Asia. Why?

Because manufacturing know-how accumulates geographically. It is not just machines — it is engineers, repair technicians, materials suppliers, testing labs, and rapid iteration cycles.

Relocating this layer means rebuilding an entire ecosystem, not just a factory.

Regionalization here often becomes “logistical relabeling,” not true structural relocation.

This is the “sticky layer” of the supply chain.

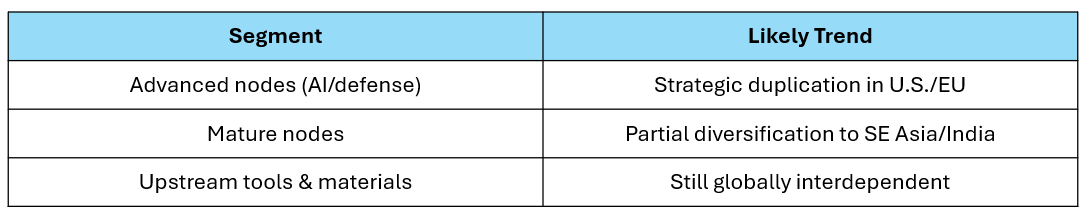

Semiconductors — Political Will vs Economic Gravity

Semiconductors are now treated as strategic assets. Governments subsidize domestic fabs, but the economics are brutal.

The report cites analysis showing localization significantly raises chip production costs. Why?

Extreme capital intensity

Skilled labor scarcity

Long supply chains for equipment & materials

High utilization requirements to break even

Advanced semiconductor production is not just a factory — it’s a national-scale ecosystem involving:

Equipment vendors

Specialty chemicals

Photomasks & substrates

Ultra-stable utilities

Decades of process learning

Thus, we observe a layered outcome:

Governments accept higher costs to ensure strategic autonomy, but full replication is economically inefficient.

ICT Hardware — Physics Determines Geography

Here, product characteristics matter more than politics.

Large, heavy systems (servers, racks, appliances):

High shipping cost

Lower precision assembly

Favor nearshoring

Small, high-density electronics (smartphones, modules):

High engineering complexity

Short iteration cycles

Remain Asia-centric

Thus ICT supply chains split:

Logistics physics + engineering density define outcomes more than ideology.

Automotive — The Emergence of Two Parallel Worlds

Automotive supply chains are becoming explicitly political.

Regulations like regional content rules and subsidy conditions effectively force supply chain bifurcation:

China-centered chain

Strong EV battery ecosystem

Cost advantages

Serving China + emerging markets

Non-China chain

Built to comply with Western policy frameworks

Excludes restricted components

Higher cost but subsidy-supported

Automotive supply chains are also flattening: OEMs now directly secure batteries and semiconductors, reducing Tier-layer dependence.

This is not just regionalization — it is systemic decoupling by regulatory design.

Government policy is increasingly reshaping the global automotive supply chain, effectively breaking the traditional long-chain model and driving a dual-track structure split between China-centered and non-China-centered systems. Because vehicles are large products and production relies on just-in-time (JIT) delivery, automotive supply chains have historically formed tight “one-day supply circles” around assembly plants, with automation helping offset rising labor costs.

However, new policy frameworks such as USMCA’s strict regional value content (RVC) requirement—mandating that 75% of components originate within the region to qualify for tariff benefits—combined with provisions in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that exclude “foreign entities of concern” (FEOC), are pushing electric vehicle batteries and key materials to localize within North America. This has accelerated the emergence of a dual-track supply chain: the “China track,” which leverages China’s mature ecosystem in batteries, power electronics, and software to deliver cost-competitive products for domestic and emerging markets; and the “non-China track,” built in North America or allied regions to comply with Western regulatory and subsidy rules, forming high-resilience supply chains that exclude Chinese components.

At the same time, the industry structure itself is flattening. The traditional multi-tier pyramid—from Tier 3 materials suppliers to Tier 1 system integrators under OEMs—is giving way to a model in which automakers directly procure core components such as batteries and semiconductors through long-term strategic agreements. This shift is reinforced by the rise of software-defined vehicles (SDVs), hardware–software decoupling, over-the-air (OTA) updates, centralized computing architectures, and modular platform design, all of which further integrate key technologies while restructuring how value and control are distributed across the automotive supply chain.

Critical Minerals: A Strategic Lever in China–U.S. Geopolitical Competition

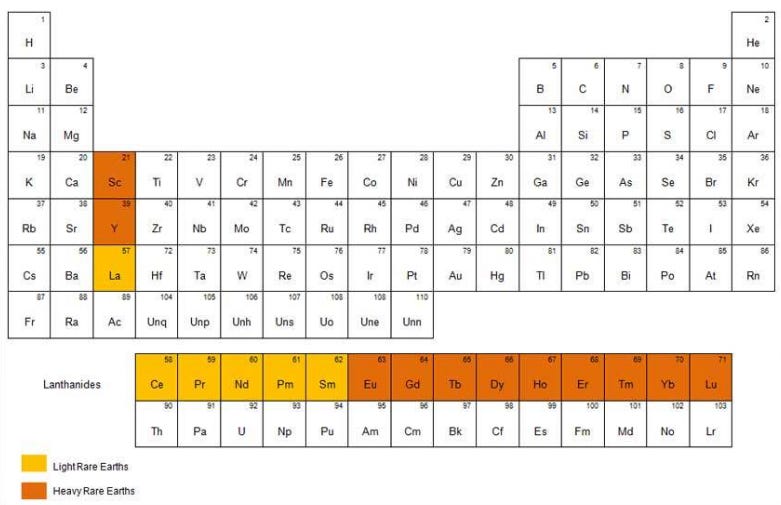

Critical minerals have emerged as one of the most powerful strategic tools in the evolving geopolitical contest between China and the United States. As the global economy accelerates its transition toward electrification, renewable energy, advanced electronics, and defense technologies, control over upstream mineral supply chains has become as important as control over manufacturing capacity.

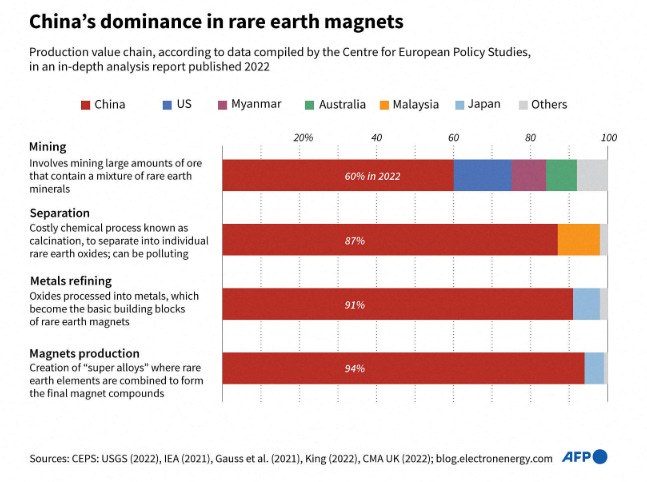

According to IEA assessments, among 20 key strategic minerals associated with the energy transition, China is the leading refining nation for 19 of them. This underscores a fundamental structural reality: while mining activity may be geographically dispersed, the processing and refining stages—where raw materials are converted into usable industrial inputs—are highly concentrated, with China holding dominant positions across multiple mineral categories. As a result, global critical mineral supply chains are not only interconnected but heavily centralized.

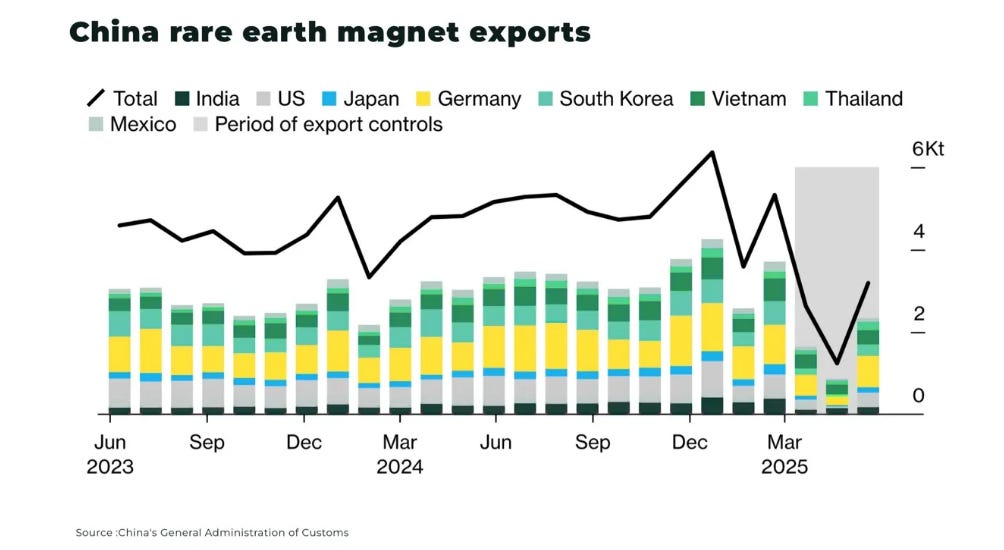

This concentration gives China significant geopolitical leverage. In response to U.S. technology restrictions, China has expanded export controls on certain rare earth metals, incorporating multiple rare earth elements into regulatory oversight. Rare earths are indispensable for high-performance magnets, electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, advanced electronics, and military systems. Control over these materials therefore translates directly into influence over downstream high-tech industries.

At the same time, the United States and its allies are attempting to rebalance this dependency. The formation of the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) reflects a coordinated effort to reduce overreliance on a single country—implicitly China—by developing alternative supply chains across North America, the Asia-Pacific, and Europe. The goal is not full decoupling, which is structurally difficult given geological realities, but diversification and risk reduction.

The structure of mineral supply chains further complicates the picture. Extraction is often tied to specific geologies: Chile for copper, Indonesia for nickel, the Democratic Republic of Congo for cobalt, and Australia for lithium. However, refining capacity—especially for lithium, rare earths, cobalt, and graphite—remains concentrated in China. This creates a layered dependency: resources may be mined globally, but processing chokepoints sit within a limited set of countries.

The strategic implication is clear: supply chain risk is shifting upstream. In earlier eras, manufacturing disruptions were the primary concern; today, the bottleneck lies in materials. Without secure access to critical minerals, downstream industries—from semiconductors to electric vehicles—cannot function, regardless of how advanced their manufacturing bases are.

Thus, critical minerals represent the new “strategic high ground” of the global industrial system. They link energy security, technological competitiveness, and national defense. While efforts to diversify supply will continue, building new mines, processing facilities, and regulatory frameworks takes years, even decades. In the near to medium term, the global economy will remain deeply dependent on existing mineral processing hubs, ensuring that critical minerals stay at the center of geopolitical strategy.

In short, the competition over critical minerals is not a side story to the technology rivalry—it is a foundational layer of it.

In the case of rare earths, the structural reality of global supply chains becomes even clearer. While mining activity is gradually diversifying— with the United States, Myanmar, and Australia expanding output and new projects emerging outside China—this shift at the extraction stage does not automatically translate into strategic autonomy. China’s position in refining remains the critical choke point. Even as global mine production spreads more widely, China continues to dominate separation, processing, and high-value downstream magnet materials, maintaining a central role in the value chain.

Projections suggest that China’s share of rare earth refining may decline from today’s near-monopoly levels, but it is still expected to remain overwhelmingly influential well into the next two decades. New refining capacity in the United States and allied countries, including projects led by companies such as Energy Fuels and Lynas, will help reduce concentration risk. However, achieving scale, technical maturity, environmental permitting, and commercial viability in rare earth processing takes years—often decades. In other words, supply diversification is a long process, not an immediate solution.

This underscores a broader lesson about critical minerals and the geopolitics of industrial transformation: upstream diversification alone does not eliminate dependence if midstream processing remains concentrated. Control over refining is control over industrial leverage. As a result, China’s influence over rare earth supply chains is likely to continue shaping the pace and structure of Western supply chain reconfiguration.

The global system is therefore entering a period where strategic competition does not sever interdependence, but rather reshapes it. Resource extraction may become more geographically distributed, yet processing hubs and technological ecosystems remain decisive. This means that efforts toward supply chain resilience will be measured not by complete decoupling—which is structurally unrealistic—but by the gradual reduction of single-point vulnerabilities.

In this new era, rare earths are not just industrial inputs; they are instruments of statecraft. The countries that control processing capacity, technological know-how, and the ability to scale alternative supply chains will define the balance of power in the energy transition and advanced manufacturing age.

The Big Picture: A Layered Global Production Map

What we are witnessing is not the collapse of globalization, but its architectural redesign.

The world economy is not breaking into sealed-off blocs. Instead, it is reorganizing into a hierarchical, layered production system, where each layer follows a different logic of mobility, risk exposure, and political sensitivity. This structure becomes especially visible when we look at critical minerals and rare earth supply chains.

At the most mobile end of the system are simple, labor-intensive manufacturing tasks, which can shift relatively quickly across borders in response to tariffs, wage differences, and trade agreements. These activities function as the shock absorbers of globalization, moving first when cost or political pressures rise.

Further up the chain lie complex industrial ecosystems—semiconductor clusters, advanced electronics networks, precision machinery hubs, and specialized chemical zones. These systems do not move easily because they depend on dense supplier networks, skilled engineers with tacit knowledge, real-time design–manufacturing coordination, and shared infrastructure. They behave more like living industrial organisms than stand-alone factories. This is why Asia continues to anchor many midstream and high-precision industries even as final assembly becomes more regionally distributed.

Above these layers are strategic nodes that governments now deliberately duplicate, despite higher costs. Advanced semiconductor fabs, battery manufacturing plants, defense electronics, and critical energy infrastructure are being replicated across regions not for efficiency, but for security. These facilities act as insurance policies—introducing redundancy and structural overcapacity, yet enhancing systemic resilience.

At the foundation of the entire system, however, lies the least mobile layer of all: raw materials. Resource extraction cannot be regionalized in the same way as manufacturing because geology does not follow political borders. Critical minerals, rare earths, and key energy resources remain geographically concentrated. This ensures that upstream interdependence persists, even as manufacturing layers reorganize.

The rare earth sector illustrates this layered reality with particular clarity. Mining is gradually becoming more diversified, with rising production in the United States, Myanmar, and Australia. Yet refining—the technologically complex stage where ores are separated into usable materials—remains heavily concentrated in China. Even if China’s share of refining declines over time, it is expected to remain dominant for years to come. Building alternative processing capacity requires scale, technical know-how, environmental permitting, and long investment cycles. Diversification is a gradual structural process, not a rapid policy switch.

This reveals a central truth of Globalization 2.0: upstream diversification alone does not eliminate dependence if midstream processing chokepoints remain concentrated. Control over refining and processing is control over industrial leverage. As a result, China’s role in rare earth and critical mineral supply chains will continue to influence how quickly and how far Western economies can restructure their supply networks.

The outcome is therefore not fragmentation into isolated blocs, but a multi-tiered global network with political constraints. Trade and interdependence persist, yet they are filtered through security reviews, subsidy rules, export controls, and alliance structures. Some flows are redirected, some duplicated, and some restricted—but the system remains connected.

Globalization 1.0 asked: Where is production cheapest?

Globalization 2.0 asks: Where is production safe enough?

The global supply chain is no longer one seamless highway optimized for speed. It is now a layered network of highways, bridges, and firewalls—slower and more expensive, but more resilient and harder to break.