Beating the Memory Wall: Inside Microsoft’s Maia 200 Strategy

Original Article By SemiVision Reserach (Microsoft, Nvidia, Google, AWS, TSMC)

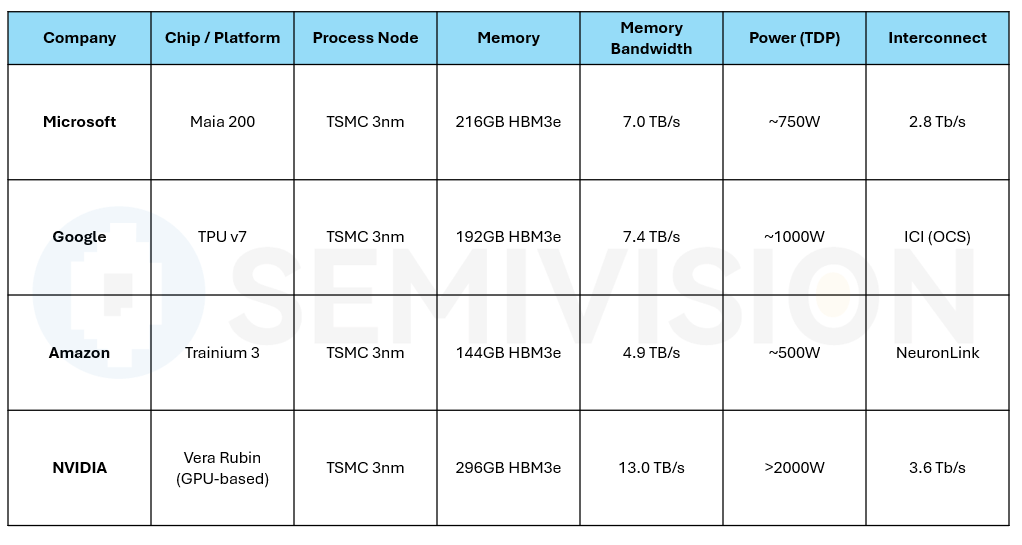

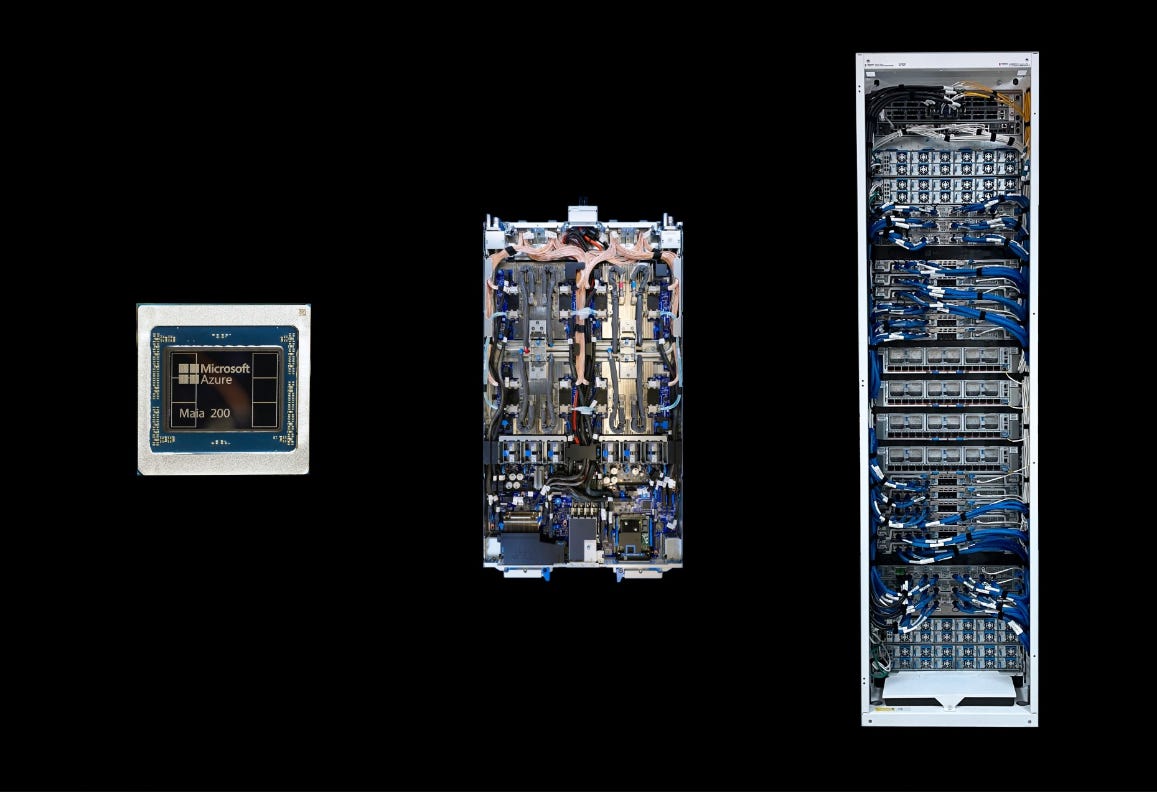

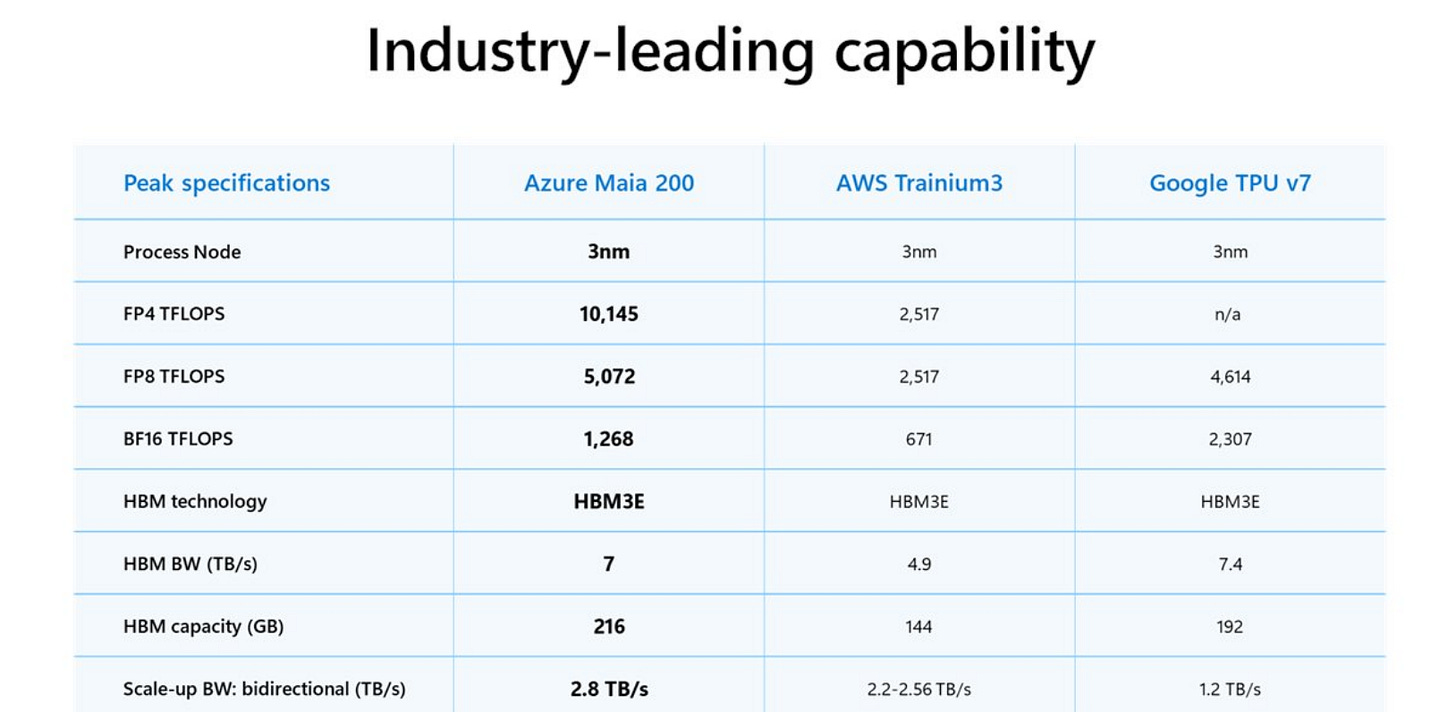

In 2026, Microsoft’s Maia 200 AI accelerator reads like an impressive report card at first glance. Its published performance metrics place it squarely in the same arena as NVIDIA’s most advanced inference platforms, and for many observers, that alone signals a dramatic shift in the competitive landscape. But interpreting Maia 200 as a sweeping, across-the-board victory over NVIDIA would be an oversimplification — and a misleading one.

Maia 200 does not represent a sudden leap in semiconductor process leadership, nor does it signal that Microsoft has outmaneuvered the industry’s established silicon giants at the level of lithography, transistor scaling, or manufacturing yield. Instead, it reveals something subtler and arguably more important: a cloud infrastructure company rethinking AI hardware not from the perspective of “maximum theoretical performance,” but from the perspective of deployable, sustainable system performance under real-world constraints.

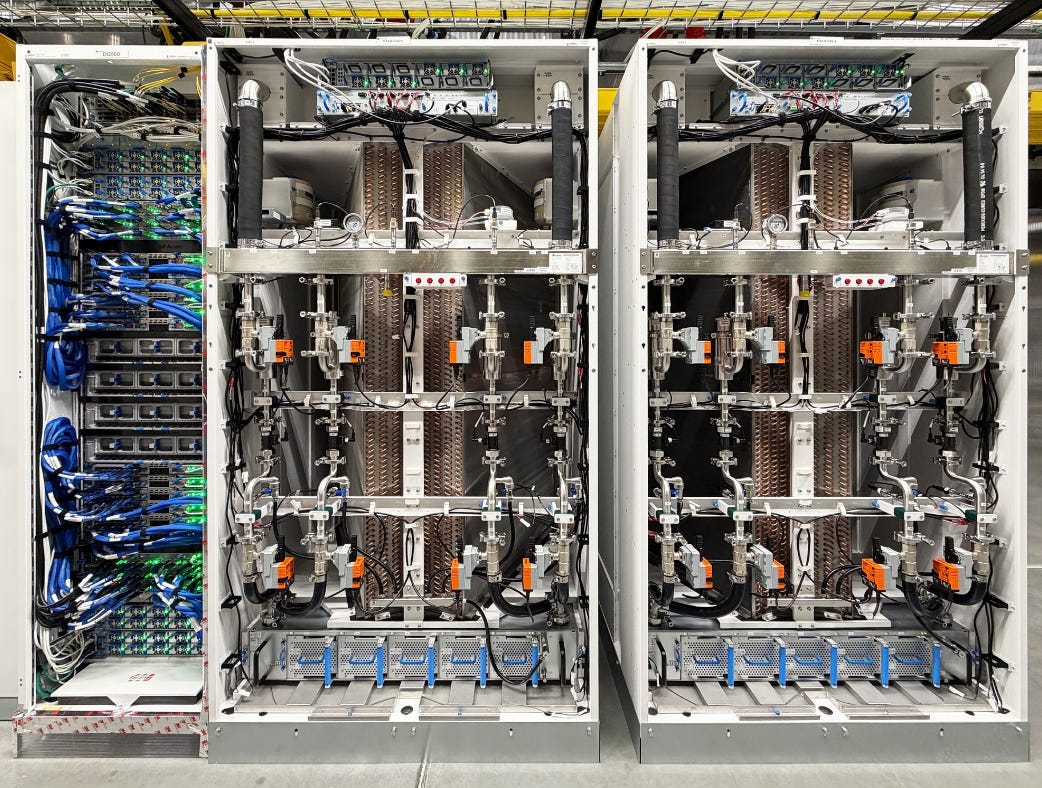

This distinction matters. The AI industry is now operating at a scale where performance is no longer limited solely by arithmetic throughput. Power delivery, cooling, memory bandwidth efficiency, interconnect topology, data center floor space, and even electrical grid capacity have become first-order constraints. In this environment, the traditional “faster is better” design philosophy begins to collide with physical and economic reality. Maia 200 emerges precisely at this intersection.

Rather than attempting to build the most universally capable accelerator or the fastest chip under ideal laboratory conditions, Microsoft pursued a third path — one that acknowledges that AI infrastructure is a system-level problem governed by trade-offs. The goal shifts from maximizing any single metric to optimizing the balance between speed, capacity, power, and cost. In this sense, Maia 200 is less an attempt to defeat NVIDIA on NVIDIA’s own terms, and more an attempt to redefine what “winning” means in large-scale AI inference.

This is why Maia 200 should not be thought of as a universal Swiss Army knife. It is not designed to excel equally across every possible model type, precision format, or future algorithmic shift. Instead, it is a highly intentional hybrid organism — part high-speed compute engine, part bandwidth optimizer, part cost-control mechanism. Its architecture is built explicitly to compensate for one of the most pressing structural weaknesses in modern AI hardware: the over-reliance on high-bandwidth memory (HBM) as both a performance enabler and a system bottleneck.

HBM has been the hero of recent AI accelerators, but it is also a source of escalating cost, power consumption, packaging complexity, and supply-chain risk. By embedding a large on-chip SRAM layer and reshaping how data flows between memory tiers, Maia 200 attempts to shift the burden away from HBM without abandoning it entirely. In doing so, Microsoft is not rejecting the prevailing architecture — it is bending it, introducing a hybrid memory philosophy that treats bandwidth not as a single number to be maximized, but as a resource to be purified, localized, and used more intelligently.

Seen in this light, Maia 200 is less a declaration of technological dominance and more a case study in architectural pragmatism. It embodies a recognition that the future of AI compute will not be decided solely by who can push transistors the smallest, but by who can best navigate the physical laws and economic pressures that now define the limits of scale.

The FP4 Accountant: Between Generality and Specialization

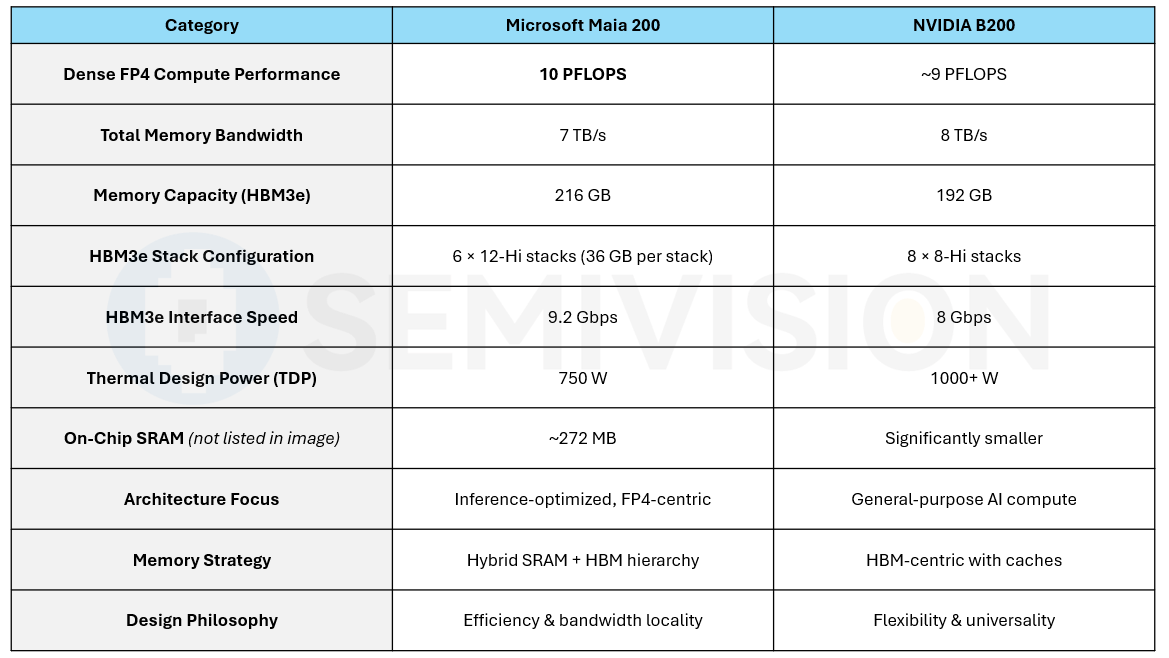

Microsoft positions Maia 200 at roughly 10 PFLOPS of dense FP4 inference performance, edging past NVIDIA’s B200 at about 9 PFLOPS. On the surface, that suggests a straightforward performance lead. But this figure comes with an enormous caveat: it represents peak performance under tightly defined inference scenarios, not across the full spectrum of AI workloads.

FP4 is an ultra-low-precision format. It dramatically reduces memory footprint, bandwidth demand, and energy per operation. When models are carefully quantized to run effectively at FP4, the computational throughput per watt can look extraordinary. In that narrow window, Maia 200 shines.

However, NVIDIA’s B200 was never designed to chase a single point on the precision spectrum. It is large, power-hungry, and expensive precisely because it must remain resilient to uncertainty. AI research does not follow a straight line. New model architectures, new attention mechanisms, and new training techniques can shift precision requirements unexpectedly. Supporting a wide range of formats — FP8, FP16, FP32, and mixed-precision modes — is insurance against the unknown.

Flexibility, in NVIDIA’s case, is not inefficiency; it is risk management.

Microsoft is taking a different position. Maia 200 embodies a bold assumption: the center of gravity for future AI inference will move toward ultra-low precision, and that the performance gains from extreme quantization will outweigh the loss of universality. This is not simply a technical choice; it is a strategic bet on the direction of the AI software ecosystem.

But specialization is a double-edged sword. Hardware that excels in one regime often underperforms when workloads drift. If future models rely more heavily on higher precision for stability, reasoning accuracy, or new algorithmic structures, Maia’s optimized FP4 datapaths could become underutilized. What appears today as architectural elegance could transform into rigidity.

In this sense, Maia 200 behaves like a financial accountant optimizing a portfolio for present market conditions. It reallocates silicon “capital” toward the most efficient operations today, squeezing out overhead and redundancy. The trade-off is reduced hedging against future volatility.

Microsoft is effectively saying: inference will dominate over training, low precision will dominate over high precision, and models will be engineered to match the hardware. If that future materializes, Maia’s efficiency gains will compound. If not, the chip’s specialization becomes a form of technical debt — difficult to amortize, expensive to redesign, and limiting in scope.

Thus, Maia 200 is not simply a faster chip in one metric. It is a statement about where Microsoft believes AI computation is heading. The difference between Maia 200 and B200 is not merely performance; it is philosophy — optimization versus optionality.

The Physical Curse of SRAM: Why 272MB Is a Luxury Limit

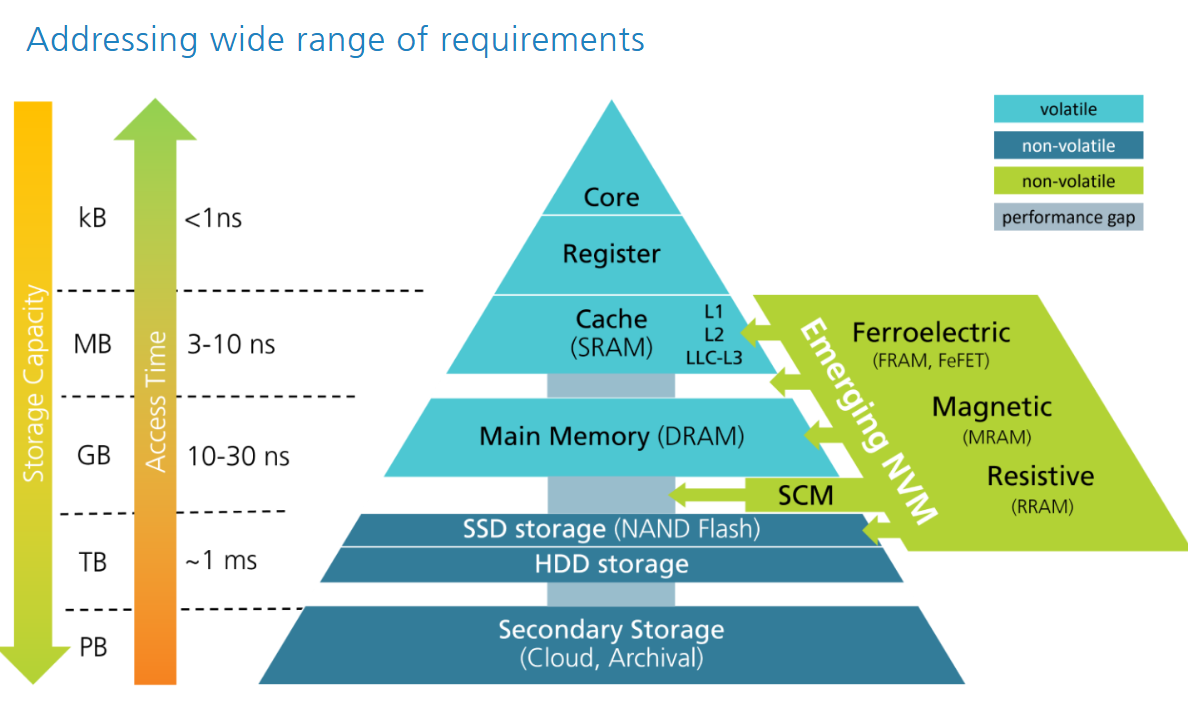

To understand why 272MB of on-chip SRAM in Maia 200 is such a remarkable — and constrained — number, we must step down from architectural diagrams into the microscopic physics of memory cells. At this scale, memory design is no longer about “faster vs. slower” or “bigger vs. smaller.” It becomes a matter of transistor geometry, charge leakage, and the fundamental trade-offs baked into silicon itself.

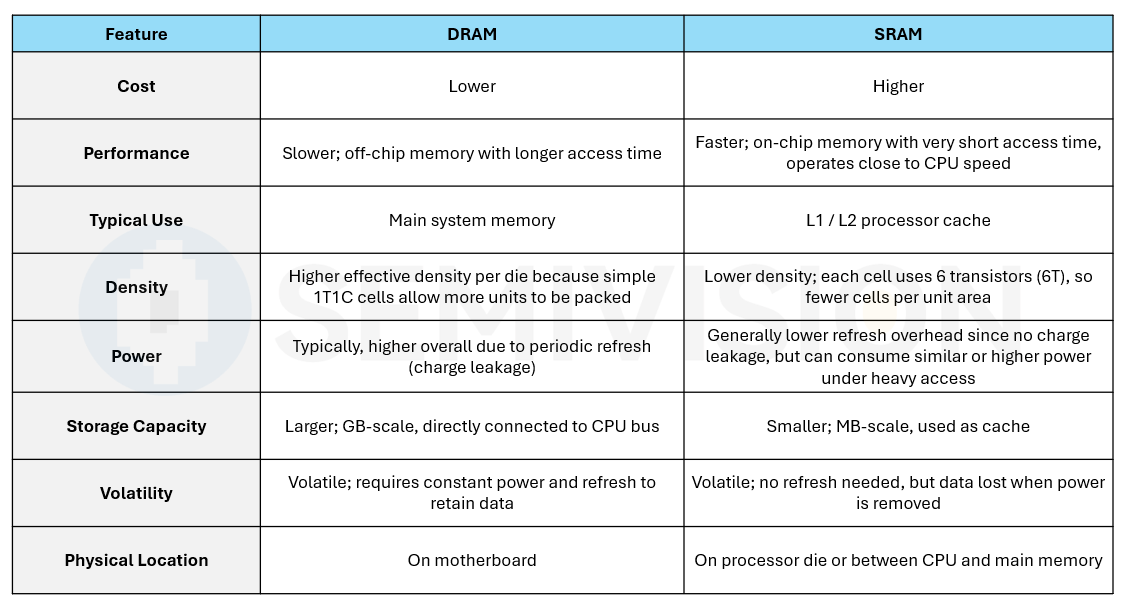

DRAM: Density Through Simplicity

Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) — including the DRAM used in HBM stacks — achieves its extraordinary capacity through radical simplicity. Each storage cell consists of just one transistor and one capacitor. The transistor acts as a switch, and the capacitor stores electrical charge representing a bit.

This minimalist design enables extreme density. DRAM cells are tiny, and because they are structurally simple, they can be stacked vertically in multiple layers. Modern HBM memory behaves like a vertical cityscape: layers upon layers of cells connected through TSVs (Through-Silicon Vias), allowing hundreds of gigabytes of memory to sit within a compact footprint.

But this density comes at a cost. The stored charge leaks. Every DRAM cell is a slowly draining bucket, requiring periodic refresh operations to prevent data loss. DRAM trades permanence and speed consistency for density.

SRAM: Stability at a Silicon Price

SRAM takes the opposite approach. Instead of storing a decaying charge, it stores data as a stable electrical state using a bi-stable latch built from six transistors (6T). This design requires no refresh; the data remains as long as power is supplied. Access latency is lower and more deterministic, and bandwidth can be extremely high when SRAM is placed close to compute logic.

But stability demands area. Six transistors occupy far more silicon real estate than one transistor plus a capacitor. The physical footprint of an SRAM bit cell is dramatically larger, and it cannot be stacked in the same vertical fashion as DRAM.

At advanced nodes such as TSMC N3E:

DRAM density can reach ~200 Mb/mm²

SRAM density is roughly ~38 Mb/mm²

This is not a marginal difference. SRAM is five to six times less area-efficient than DRAM. In chip design terms, every additional megabyte of SRAM is a direct subtraction from the silicon area available for compute cores, interconnect fabric, or I/O structures.

The Die Area Wall

This density gap explains why an “all-SRAM” architecture, like the one pursued by Groq, is extraordinarily difficult to scale. A design that attempts to replace high-capacity external memory with on-die SRAM quickly runs into a physical wall:

Die size grows beyond reticle limits.

Yield drops because large dies are more prone to defects.

Cost per chip skyrockets, often faster than performance gains.

Even if technically feasible, such a chip may be economically unsustainable at hyperscale deployment volumes.

Why 272MB Is a Ceiling, Not a Choice

Seen in this context, Maia 200’s 272MB of SRAM is not an arbitrary design flourish — it is a negotiated truce between physics and architecture. It represents a point where:

On-chip memory is large enough to hold critical working sets and reduce HBM traffic

Compute logic area remains sufficient for meaningful throughput

Die size stays within manufacturable and yield-tolerant bounds

Power density does not exceed cooling capabilities

Adding more SRAM would not simply “improve performance.” It would displace compute resources, increase cost per wafer, lower yield, and raise thermal density. Beyond a certain point, more SRAM begins to degrade system efficiency rather than improve it.

Thus, 272MB is a luxury limit — a boundary defined not by marketing ambition but by the geometry of transistors and the economics of lithography. It is the maximum Microsoft could deploy without tipping the balance between memory locality and silicon practicality.

Bandwidth Purity: The Hidden “Water Weight” of HBM

If SRAM is so expensive and area-hungry, why include so much of it?

The answer lies in the quality of bandwidth.

HBM bandwidth figures look impressive on paper, but DRAM behaves like a leaky bucket. It requires periodic refresh cycles (tREFI and tRFC), consuming roughly 8% of bandwidth. Add row conflicts and page misses, and theoretical bandwidth can never be fully realized.

SRAM is different. It requires no refresh and sits on the same die as the compute cores. Its theoretical bandwidth is effectively its real bandwidth.

Maia 200’s SRAM (TSRAM + CSRAM) forms a zero-wait, high-purity bandwidth layer. Although its HBM bandwidth (7 TB/s) is slightly lower than B200’s (8 TB/s), the effective bandwidth during real workloads may be higher because most hot data never leaves SRAM.

CSRAM and TSRAM: Class Mobility Inside the Chip

Microsoft divides its SRAM into two “classes”:

TSRAM: The Local Working Class of Data

Tile-level SRAM (TSRAM) sits directly next to compute tiles — the neighborhoods where arithmetic actually happens.

Key Characteristics

Proximity to compute

TSRAM is physically integrated alongside the execution units. Data does not travel through long interconnect paths or off-chip interfaces.Bandwidth grows with compute

As more compute tiles are added, each brings its own SRAM slice. Bandwidth therefore scales naturally with compute density, not with package I/O limits.Ultra-low latency

This memory tier holds the hottest working data — activations, intermediate tensors, and partial results.

Functional Role

TSRAM behaves like an ultra-wide, ultra-fast scratchpad. It minimizes the need for repeated trips to higher memory tiers. For inference workloads, where many operations repeatedly reuse small sets of data, TSRAM becomes the primary execution workspace.

It is the equivalent of giving every worker their own high-speed desk rather than forcing everyone to share a central warehouse.

CSRAM: The Coordinating Middle Class

Above TSRAM sits Cluster-level SRAM (CSRAM), which functions as a shared coordination layer across multiple tiles.

Key Characteristics

Global visibility within the chip

CSRAM is accessible to multiple compute tiles, acting as a staging and exchange zone.Moderate latency, high flexibility

While slightly slower than TSRAM, CSRAM still operates entirely on-chip, avoiding the penalties of HBM access.Data orchestration role

It stores shared model parameters, routing buffers, scheduling metadata, and intermediate data that must move between tiles.

Functional Role

CSRAM is not about raw speed at the per-core level. It is about system coherence. It ensures that data produced in one tile can be efficiently reused elsewhere without falling back to HBM.

Think of CSRAM as the logistics center that coordinates traffic between neighborhoods, preventing congestion on the highway to external memory.

The Architectural Insight

This two-class SRAM design reflects a broader insight: in modern AI accelerators, performance is no longer determined only by compute FLOPS or raw HBM bandwidth. It is determined by where data lives most of the time.

TSRAM and CSRAM together form a bandwidth amplification system. They allow Maia 200 to extract more real performance from less external bandwidth by reducing data travel distance.

In effect, Microsoft is not just adding more memory — it is redesigning the social structure of data inside the chip.

HBM: The Necessary Evil That Prevents Bankruptcy

Groq demonstrated that all-SRAM designs achieve extraordinary speed. It also demonstrated the cost: limited capacity (hundreds of MB) and the need to string together thousands of chips for large models, driving exponential system complexity.

Microsoft took the pragmatic route. Maia 200 retains 216GB of HBM3e — a sober decision. In 2026, LLMs contain hundreds of billions of parameters. Pure SRAM architectures are economically infeasible.

HBM becomes the large, slower reservoir. SRAM becomes the fast workspace. This is classic hierarchical memory — balancing cost and performance rather than chasing purity.

The Middle Path of AI Chip Design

Maia 200 is not the most visually dramatic chip in the industry. It does not chase Groq’s philosophy of extreme, all-SRAM speed, nor does it match the universal flexibility of NVIDIA’s B200. Its achievement lies elsewhere — in a deeper understanding of the physical realities that govern modern AI hardware and a willingness to design with those constraints rather than against them.

At the heart of Maia’s architecture is a clear division of labor:

SRAM delivers refresh-free, high-purity bandwidth, keeping hot data close to computation and minimizing wasted cycles.

HBM delivers density at a sustainable cost, providing the large-capacity backbone required for modern AI models.

Hybrid memory transforms physical limitations into architectural advantages, shifting the performance equation from brute-force bandwidth toward intelligent data locality.

This is not a design that attempts to break the rules of physics. It is a design that accepts them — and then bends them through hierarchy, locality, and balance.

As AI models continue to grow in size and complexity, this approach becomes increasingly relevant. Simply increasing HBM stacks is not indefinitely scalable in cost, power, or packaging complexity. Instead, we are likely to see a gradual shift:

Larger on-chip SRAM pools

Smarter memory hierarchies

Reduced reliance on raw external bandwidth

Greater emphasis on where data lives, not just how fast it can move

In this emerging landscape, the future of AI silicon may not belong to the chip that is the fastest under ideal conditions, nor to the one that can do everything equally well. It may belong to the architectures that best balance physics, economics, and workload reality — systems that treat memory not as a bottleneck to overpower, but as a structure to reorganize.

Maia 200 is an early example of that middle path.