Viewing Japan’s Semiconductor Strategy Through Takaichi’s Lens of Economic Security

Original Article By SemiVision Research

Viewing Japan’s Semiconductor Strategy Through Takaichi’s Lens of Economic Security

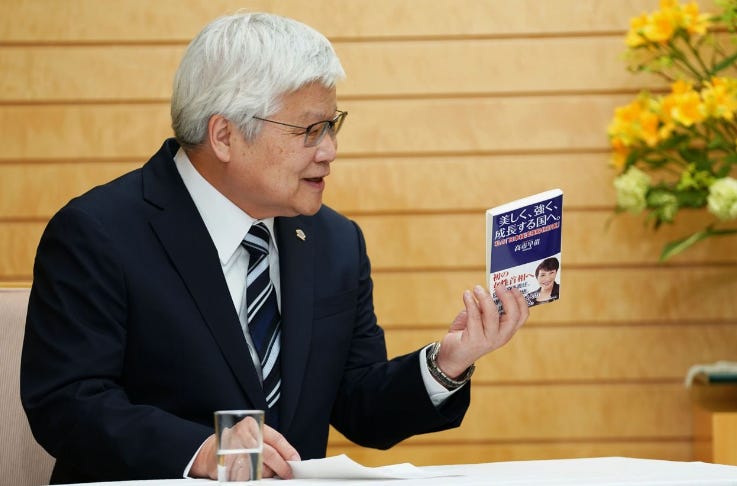

During this meeting with the Japanese government, C.C. Wei brought along a copy of Sanae Takaichi’s book. At the time it was written, Takaichi had been one of the strongest advocates for inviting TSMC to invest and build fabs in Japan as a way to revitalize the Japanese economy and return the country to a growth trajectory in semiconductors. The book has since come to be regarded as a “political blueprint” for TSMC’s investment in Japan.

When Takaichi saw Wei take out the book, she reportedly burst into laughter, joking that her jaw nearly dropped.

Wei emphasized, “I am a loyal supporter of Ms. Takaichi. In fact, the book you wrote five years ago already strongly supported TSMC and explicitly discussed our role.”

For many years, Japan has lacked advanced chip manufacturing capabilities below the 10-nanometer node. The potential introduction of TSMC’s 3-nanometer production in Kumamoto would help close this long-standing technology gap and carry significant symbolic importance for Japan’s economic security.

TSMC originally planned for its second fab in Kikuyo Town, Kumamoto Prefecture, to manufacture chips using 6- to 12-nanometer process technologies. Under the revised plan, the facility is now being upgraded to a 3-nanometer process. As a result, capital expenditure for the still-under-construction second fab is expected to increase from approximately US$12.2 billion to US$17.0 billion.

The facility is projected to enter production in 2028. As global competition in AI computing power continues to intensify, advanced-node manufacturing capacity has become a strategic resource fiercely contested by nations. In recent years, the Japanese government has significantly expanded its subsidy programs and proactively encouraged TSMC to scale up its investments, successfully enabling the localization of 3-nanometer production. Beyond stimulating the formation of local ecosystems for equipment, materials, and talent, this move also strengthens Japan’s role as a critical node in the global semiconductor supply chain.

Sanae Takaichi’s Policy Blueprint

Toward a Beautiful, Strong, and Growing Nation: My Plan for Japan’s Economic Resilience

This book is not a conventional work on economic policy. Rather, it is a highly politicized, national-security-oriented blueprint for restructuring Japan’s economic system. Takaichi’s core objective is to redefine a fundamental question:

What does “successful economic policy” actually mean in an era of geopolitical risk?

In her framework, economic growth is no longer the ultimate goal. Instead, growth becomes the outcome of national survival, strategic autonomy, and institutional resilience.

The Core Problem:

Japan Is Using a “Peacetime Economy” to Face a High-Risk World

At the heart of Takaichi’s argument is a structural diagnosis she believes Japan has long ignored:

Japan’s economic system was designed under the assumption of a low-risk, smoothly functioning globalized world.

That assumption no longer holds.

She points to a series of irreversible shifts:

The long-term intensification of U.S.–China strategic rivalry

The weaponization of supply chains (semiconductors, energy, critical minerals)

Rising risks of technology leakage and industrial hollowing-out

Increasing frequency of pandemics, natural disasters, and armed conflicts

Under such conditions, an economic system optimized purely for efficiency and cost minimization becomes inherently fragile.

From this perspective, economic resilience is no longer optional—it is a prerequisite for national transformation.

I. Core Philosophy:

Economic Security Is Not an Add-On — It Is the Starting Point

Takaichi’s most distinctive—and controversial—argument is simple but radical:

Economic policy itself must be national security policy.

This leads to three fundamental shifts in policy logic.

1. Free Trade Is Conditional, Not Absolute

She does not reject free trade. However, she insists that:

Free trade must not create single-point dependencies

Market efficiency cannot override national survival

2. Industrial Policy Must Serve “Survival Capacity”

Policy should no longer focus only on:

Profitability

Short-term competitiveness

But also ask:

Can the nation survive supply disruptions?

Can it maintain production during crises?

3. Strategic Sectors Must Be Treated as National Assets

She explicitly identifies:

Semiconductors

Energy

Food security

Communications infrastructure

Key advanced technologies

These areas, she argues, cannot be left entirely to market forces.

II. Industrial Policy:

From Comparative Advantage to Strategic Necessity

Takaichi offers a sharp critique of Japan’s long-standing industrial self-image as merely a high-value component and technology supplier.

The risks of this model include:

Offshoring of manufacturing bases

Loss of system-level control

Strategic choke points located outside Japan

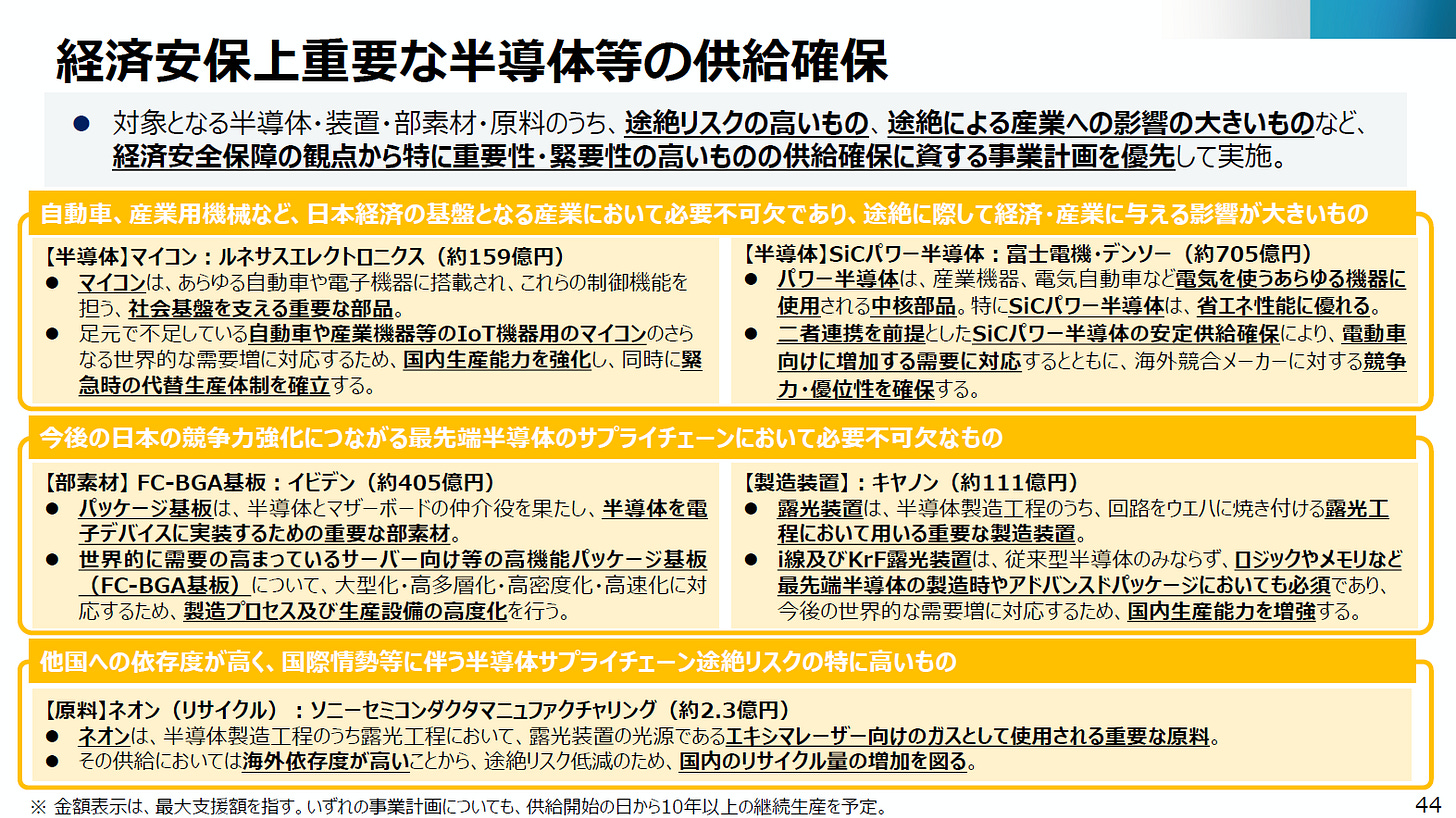

1. Semiconductors and Advanced Manufacturing

Her stance is not full reshoring, but strategic redundancy:

Critical nodes must exist domestically

Zero-backup dependency is unacceptable

She supports domestic capability in:

Wafer fabrication

Key materials

Process equipment

Allied cooperation rather than unilateral dependence

2. Protection of Strategic Technologies

She argues Japan has been overly naïve in:

Investment screening

Technology leakage risk assessment

Responding to hostile acquisitions

She therefore advocates:

Stronger foreign investment review mechanisms

Export controls on sensitive technologies

Clear identification of dual-use (civil–military) technologies

3. Strategic Stockpiling of Critical Materials

In her words:

A country without strategic reserves is not a fully sovereign nation.

She calls for national-level reserves of:

Rare earths

Energy resources

Pharmaceuticals

Food supplies

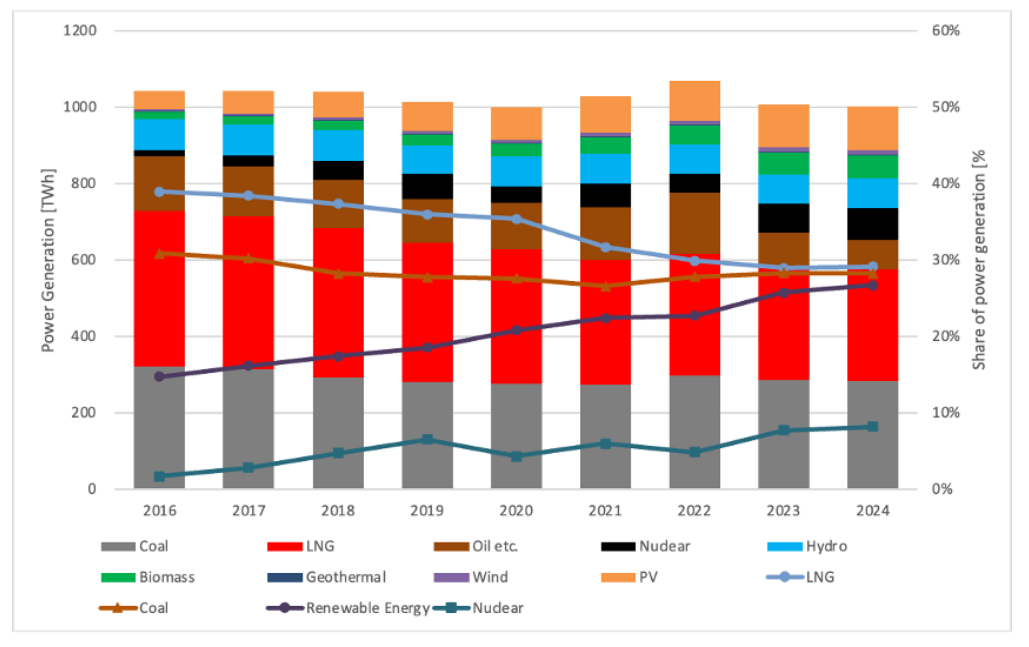

III. Energy Policy:

Energy Is Not an Environmental Issue — It Is a Power Issue

Takaichi’s energy stance is unambiguous:

Heavy dependence on imported energy is a national security vulnerability

Idealistic, unconditional nuclear phase-out is strategically self-defeating

Her proposal is not a return to old nuclear models, but:

Nuclear restart with technological upgrades

Integration with hydrogen and next-generation energy systems

A stable, controllable, and predictable energy mix

In her framework, energy security is the foundation of industry, defense, and social stability.

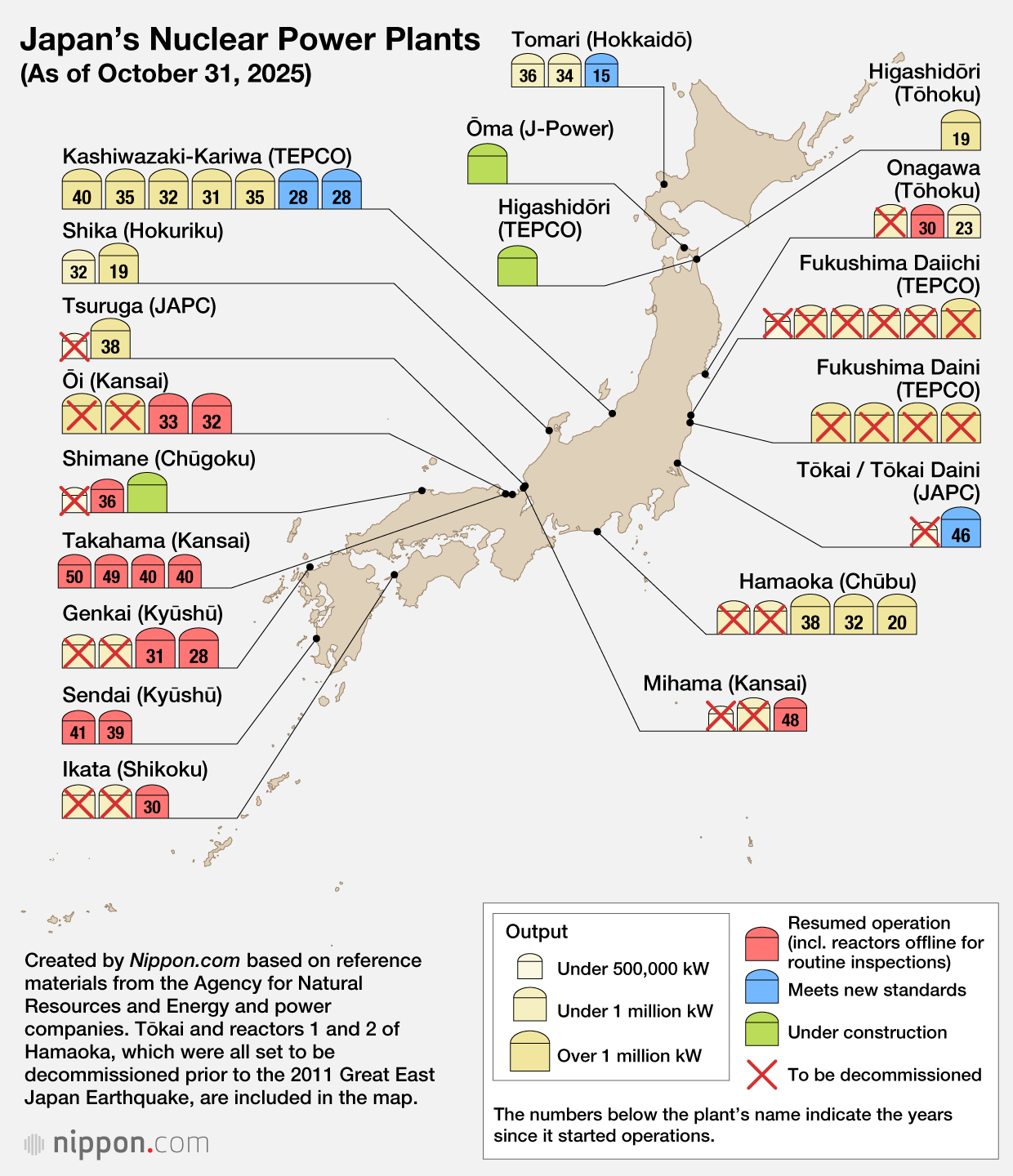

With demand for electricity expected to rise due to factors including the construction of more data centers to power generative AI services, the government stated in its basic energy plan, approved by the cabinet in February, that it would make maximum use of Japan’s existing nuclear power plants. It set a goal of increasing nuclear power from its current level of supplying less than 10% of total energy to around 20% by fiscal 2040.

Since the 2011 disaster, only 14 of the existing 36 nuclear power reactors (including those under construction) have restarted. In eastern Japan, only the number 2 reactor at Tōhoku Electric Power Company’s Onagawa Nuclear Power Station is operating.

In August, the government announced that it would expand financial support for local authorities in the vicinity of nuclear power plants from those within a 10-kilometer radius to those up to 30 kilometers away. At the Niigata prefectural assembly in October, it was also stated that the national government would cover all costs of building evacuation routes from Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station. Meanwhile, TEPCO announced that it would contribute ¥100 billion to encourage the creation of new enterprises and jobs. The Niigata prefectural government approved these moves and accepted the restart of the plant.

IV. Technology and Institutional Capacity:

National Power Is About Systems, Not Just Innovation

She defines technological strength as a three-layer system:

Basic research capacity (long-term investment)

Industrialization capability (lab-to-mass-production)

Institutional absorption capacity (regulation, cybersecurity, governance)

Accordingly, she emphasizes:

STEM talent development

Civil–military technology integration

Digital government

Information and cybersecurity infrastructure

This thinking directly aligns with Japan’s later Economic Security Promotion Act.

V. Fiscal Philosophy:

Distinguishing Strategic Investment from Waste

Takaichi is not an indiscriminate spending advocate. However, she firmly rejects fiscal austerity that undermines national capability.

Her key distinction is this:

Spending that strengthens long-term productivity and national security is investment, not waste.

Thus, she supports sustained fiscal commitment to:

Semiconductors

Energy

Strategic technologies

Defense-related industries

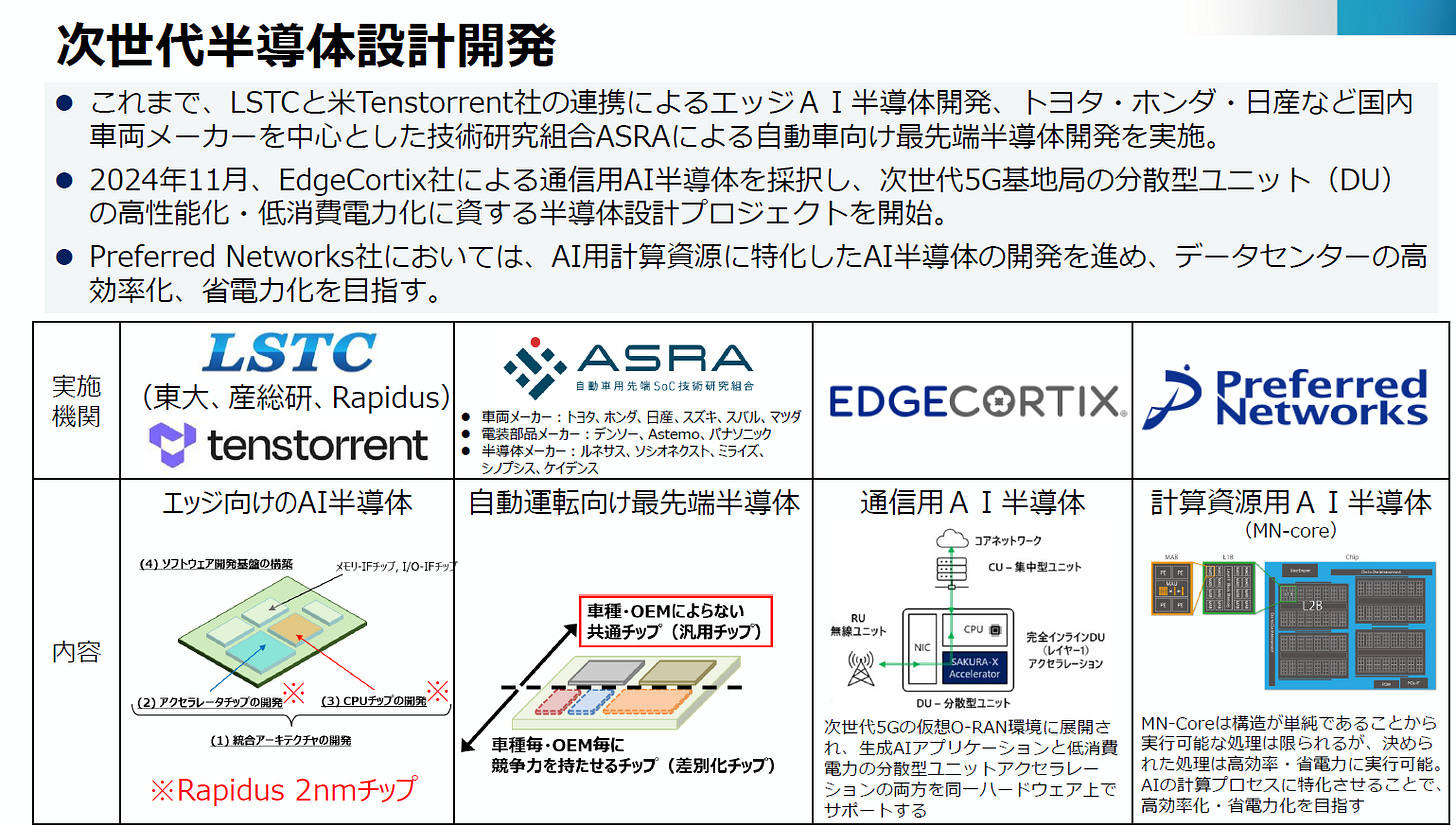

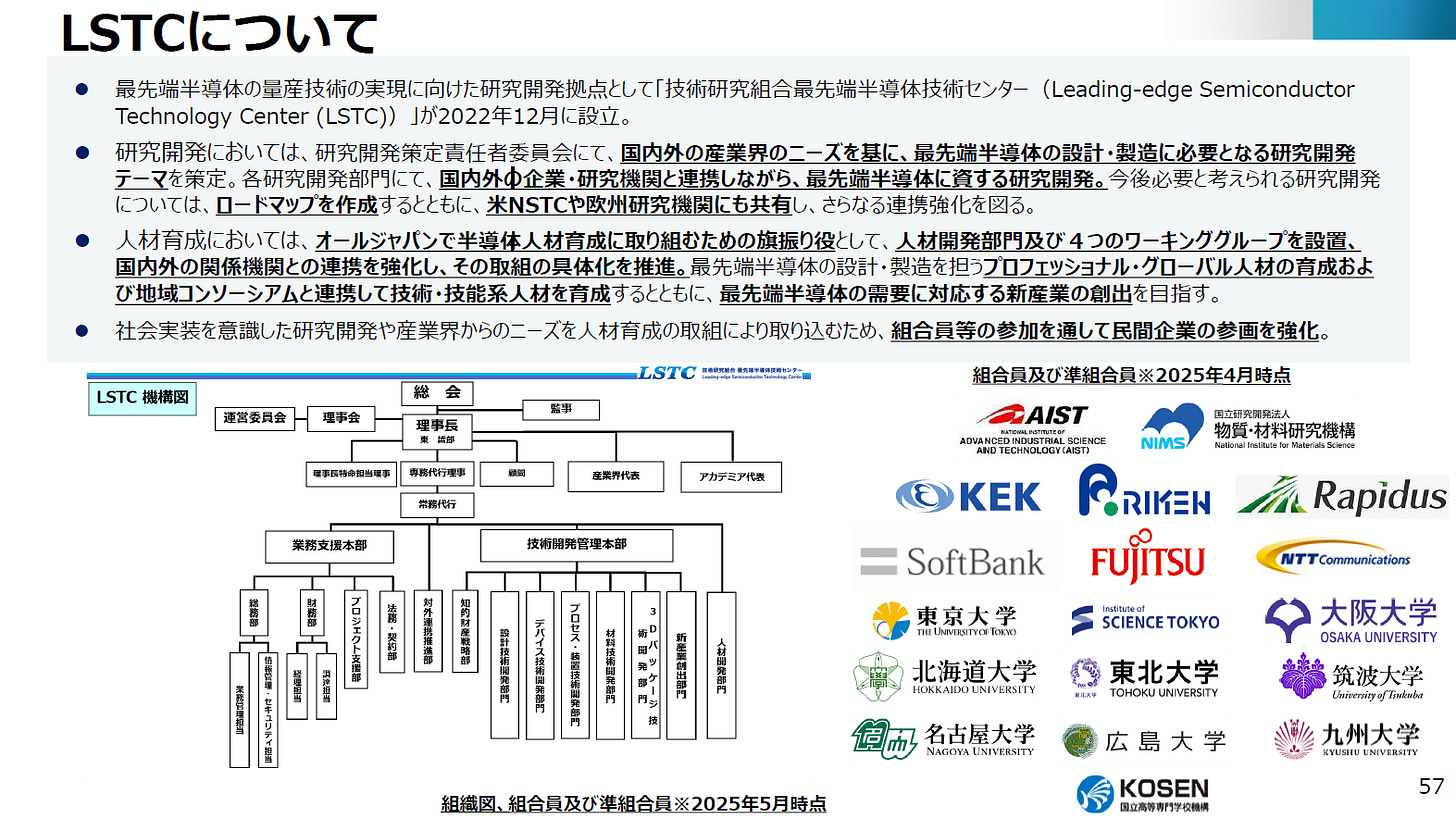

Securing the Supply of Economically Critical Semiconductors

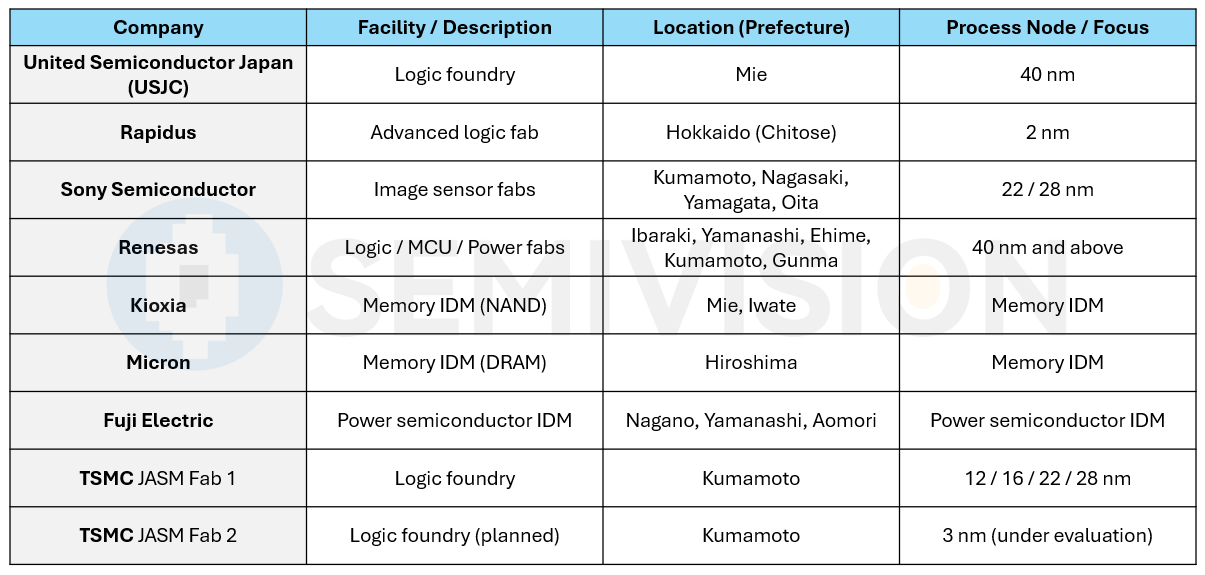

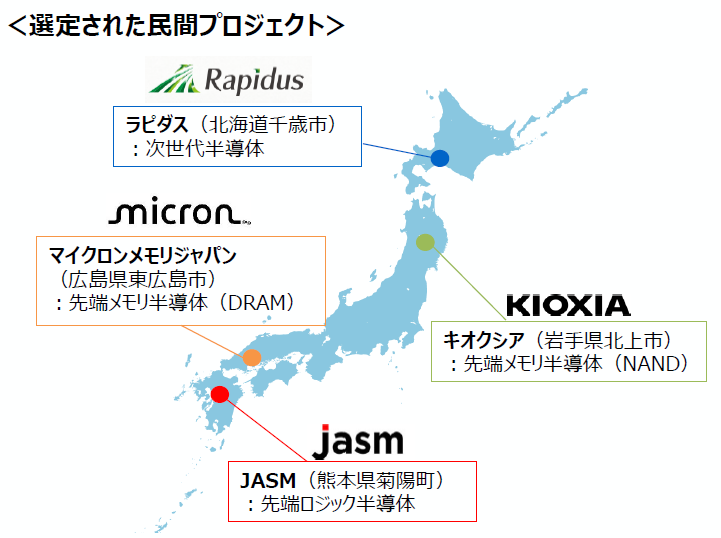

This slide outlines Japan’s strategy to secure the supply of semiconductors and related materials that are essential to economic security. The policy prioritizes components, equipment, and raw materials with high supply disruption risk and large potential impact on industry and the economy.

For core industries such as automotive and industrial machinery, Japan is strengthening domestic production capacity to ensure stable supply during emergencies. This includes support for microcontrollers (MCUs) used in vehicles and IoT devices, as well as SiC power semiconductors critical for electric vehicles and energy-efficient industrial systems.

To enhance long-term competitiveness in advanced semiconductor supply chains, Japan is also investing in key packaging materials like FC-BGA substrates and manufacturing equipment such as lithography tools. These technologies are vital for high-performance computing, servers, and advanced logic and memory production.

In addition, Japan is addressing vulnerabilities in raw materials with high overseas dependence. A key example is neon gas, essential for semiconductor lithography, where domestic recycling capacity is being expanded to reduce supply disruption risks.

Overall, the initiative reflects a shift from pure cost efficiency toward resilience, redundancy, and economic security, with long-term commitments to domestic production and supply stability.

VI. Japan’s International Positioning:

From Neutral Economic Actor to Alliance-Based State

Her geopolitical stance is clear:

Deepen alliance integration with the United States

Build supply chain networks with like-minded nations

Abandon strategic ambiguity in favor of clarity

In her view:

Economic policy, foreign policy, and defense policy are inseparable components of a single system.

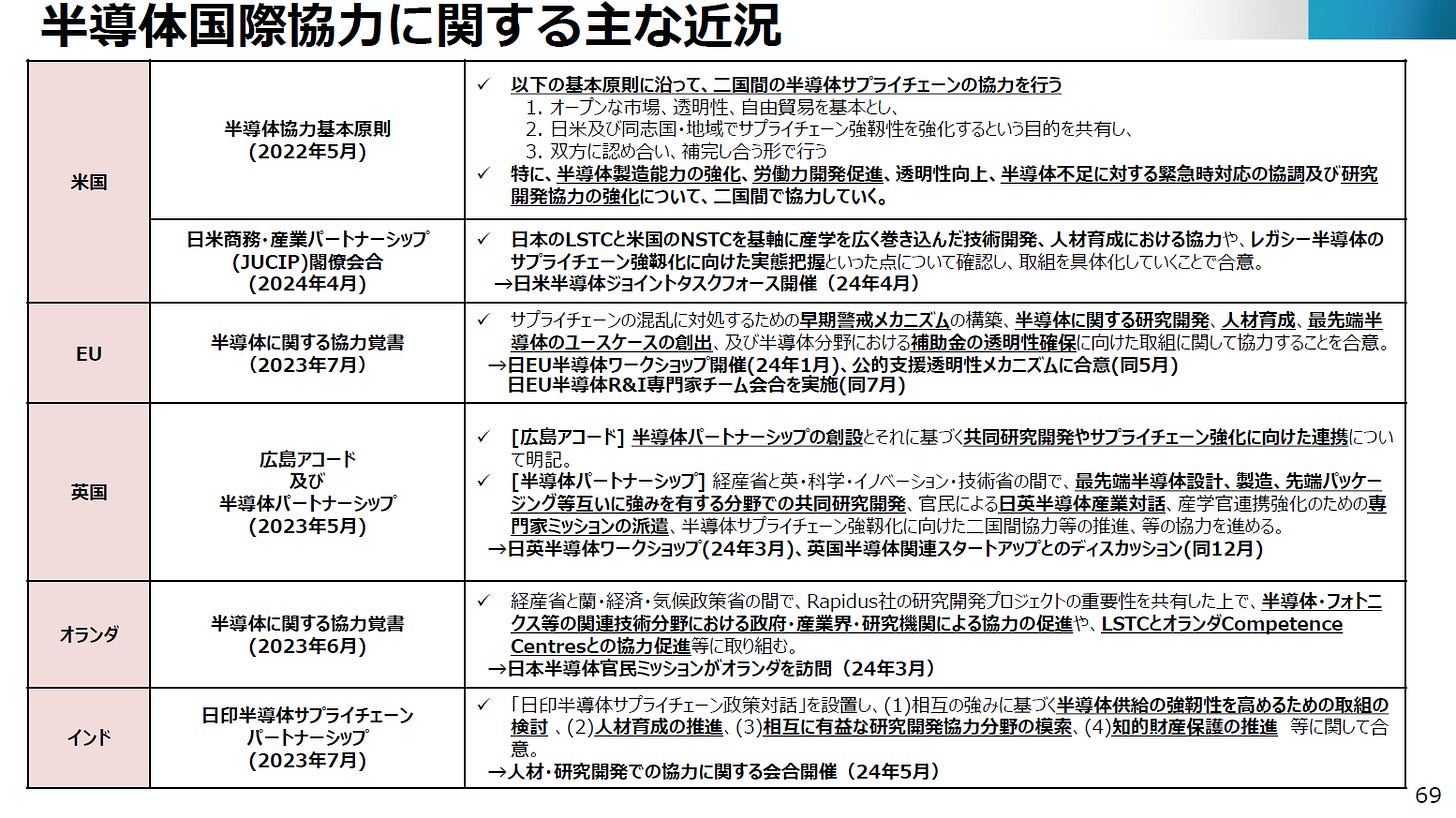

Key Developments in International Semiconductor Cooperation

United States

Japan and the United States have established a framework for semiconductor cooperation based on shared principles such as open markets, transparency, and free trade. Both sides aim to strengthen supply chain resilience across allied countries and regions through complementary roles. Cooperation focuses on reinforcing semiconductor manufacturing capacity, labor development, supply chain transparency, emergency response to shortages, and joint research and development. These efforts are advanced through platforms such as the Japan–U.S. Commercial and Industrial Partnership (JUCIP), with concrete initiatives in technology development, talent cultivation, and legacy semiconductor supply chain stabilization.

European Union

Japan and the EU have signed a memorandum of cooperation on semiconductors to enhance supply chain resilience and reduce disruption risks. Key areas include early warning mechanisms for supply chain shocks, joint research and development, talent development, and collaboration on advanced semiconductor use cases. The partnership also emphasizes transparency in public subsidies. This cooperation has been institutionalized through Japan–EU semiconductor workshops, agreements on public support transparency, and expert-level R&D dialogues.

United Kingdom

Under the “Hiroshima Accord” and a bilateral semiconductor partnership, Japan and the UK are strengthening collaboration in advanced semiconductor design, manufacturing, and advanced packaging. The partnership promotes joint research, industry–academia collaboration, talent exchange, and supply chain resilience. It also supports the expansion of semiconductor startup ecosystems and facilitates policy coordination through workshops, expert missions, and innovation-focused exchanges.

Netherlands

Japan and the Netherlands have agreed on semiconductor cooperation covering advanced manufacturing technologies, including photonics and next-generation chips. The partnership emphasizes collaboration among governments, industry, and research institutions, particularly in areas related to Rapidus’ R&D efforts. Cooperation also includes talent development and joint work between Japan’s LSTC and Dutch competence centers, reinforcing ties in critical semiconductor equipment and technology domains.

India

Japan and India have launched a semiconductor supply chain partnership aimed at strengthening supply resilience based on their respective strengths. The cooperation focuses on talent development, mutually beneficial joint R&D, promotion of intellectual property protection, and policy coordination through a dedicated bilateral dialogue. Regular meetings support collaboration in human resources and research activities, positioning India as a long-term partner in diversified semiconductor supply chains.

Final Synthesis: From Economic Efficiency to Strategic Autonomy

This book is not about how Japan can grow GDP faster.

It is about something more fundamental:

How Japan can remain autonomous, productive, defensible, and sustainable in a world defined by systemic risk.

It represents a decisive ideological shift:

From efficiency-first globalization

To security-first national economics

From passive globalization benefits

To active resilience competition

This is precisely why Takaichi’s ideas resonate so strongly today—at a moment when supply chain restructuring, semiconductor competition, energy security, and economic security legislation have all moved to the center of global policy debates.

Semiconductor Policy as Economic Security in Action

Global foundry leader TSMC has recently made significant progress in its Japan strategy. On the 5th, Chairman C.C. Wei met directly with Prime Minister Takaichi to conduct in-depth discussions on TSMC’s ongoing and future investments in Japan.

During the meeting, Wei revealed that surging global demand for AI and high-performance computing (HPC) chips has forced TSMC to reassess its global capacity allocation. The second fab under construction in Kumamoto—originally planned for 6-nanometer and specialty nodes such as 12/16nm—is now actively being evaluated for a potential leap directly to 3-nanometer production.

If confirmed, this would mark the first time TSMC deploys its most advanced leading-edge process in Japan.

Wei emphasized that this reassessment is not speculative. Construction at the second Japan Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing (JASM) site is already underway, and the shift reflects a structural change in global demand rather than a short-term cycle. AI workloads, HPC accelerators, and advanced logic chips are redefining what “strategic capacity” means.

He also expressed explicit gratitude to Japan’s central government, Kumamoto Prefecture, and local communities, underscoring that long-term political commitment and social support are the foundation enabling such high-stakes investments. Japan’s forward-looking semiconductor policies, in his view, will generate strong spillover effects across the domestic supply chain and further deepen strategic partnerships with companies such as Sony.

From Mature Node Champion to Advanced Manufacturing Core

TSMC’s Japan presence is currently structured in two phases. The first fab reached mass production by the end of 2024. The second was initially designed to support a mix of 6nm, 12/16nm, and 22/28nm processes, but is now under evaluation for conversion to 3nm.

Industry analysts note that if Kumamoto formally adopts 3nm, Japan will cross a historic threshold. It would signal a transition from being primarily a mature-node manufacturing powerhouse to becoming a country with leading-edge mass-production capability.

For TSMC, this enhances global risk diversification and capacity-allocation flexibility. For Japan, it represents something far larger: the materialization of economic security as industrial reality.

The Deeper Meaning of Takaichi’s Vision

Seen through the lens of Takaichi’s book, this development is not merely an investment decision—it is ideological consistency.

Advanced semiconductors are no longer neutral commodities. They are strategic assets that determine national competitiveness, military capability, industrial sovereignty, and long-term productivity. By anchoring leading-edge manufacturing capacity domestically, Japan is no longer optimizing for cost alone, but for continuity under stress.

This is the essence of the shift the book describes:

Not faster growth—but safer growth.

Not maximum efficiency—but controlled redundancy.

Not dependence—but strategic autonomy.

Japan’s semiconductor strategy, exemplified by TSMC’s evolving Kumamoto plan, shows that economic security is no longer a theory. It is being poured into concrete, etched into silicon, and scaled for the realities of a fragmented world.

And in that sense, the book’s argument does not conclude on its final page—it continues, quite literally, on the factory floor.