When Chips Meet Geopolitics: TSMC and the Silicon Shield Debate

Original Article By SemiVision Research

When people around the world talk about Taiwan’s role in the semiconductor industry, one name almost always comes first: TSMC. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company sits at the very center of the global chip supply chain, producing the world’s most advanced logic chips — the processors that power smartphones, data centers, AI accelerators, and next-generation computing platforms. In many ways, TSMC is not just a company; it is a foundational infrastructure layer of the digital economy, comparable to a global utility for computation.

Because of this central position, TSMC’s manufacturing capacity has taken on a meaning far beyond business. It has given rise to a popular geopolitical idea known as the “Silicon Shield” — the belief that Taiwan’s critical importance to global semiconductor supply would deter military conflict. The logic is straightforward: if the world’s most advanced economies depend on chips made in Taiwan, then major powers would have strong incentives to prevent instability that disrupts that supply.

But according to former TSMC R&D executive Yang Kuang-Lei, this idea is deeply misunderstood — and even unwanted by TSMC itself.

TSMC Does Not Want to Be a “Shield”

Speaking in an interview, Yang stated bluntly that TSMC has no interest in becoming a “Silicon Shield.”

“Why would I want to stand on the front line of a war and be used as a shield?” he said

From TSMC’s perspective, the company is a business, not a geopolitical instrument. Its identity is built around manufacturing excellence, global customer service, yield optimization, and technology leadership. Its mission is to fabricate chips better and more reliably than anyone else — not to serve as a strategic deterrence tool. In Yang’s framing, turning TSMC into a symbolic shield effectively places the company at the center of geopolitical confrontation, a role that no enterprise would voluntarily choose.

He emphasizes that TSMC’s natural orientation is globalization. Its business model depends on serving customers from the U.S., Europe, Japan, and increasingly other regions. The company’s success comes from being a trusted neutral manufacturing partner — a kind of Switzerland of advanced logic fabrication. Strategic symbolism, especially in a military sense, runs counter to that positioning.

A Taiwanese Idea, Not an American One

Yang further argues that the Silicon Shield concept was largely a Taiwanese interpretation of risk, not an American one.

For Taiwan, the logic was intuitive: if the world depends on our chips, the world will protect us. Semiconductor manufacturing becomes a form of insurance policy — a high-tech version of “too important to fail.” But Yang notes that this line of thinking reflects Taiwan’s perspective, not necessarily Washington’s.

From the U.S. point of view, the core issue is not how to protect Taiwan because of chips; it is how to ensure access to chips regardless of what happens. That is a fundamentally different risk calculation. The United States does not view semiconductors as a magical deterrent that can prevent conflict. Instead, it treats them as a strategic dependency that must be managed, diversified, and partially localized.

In this sense, the American response — encouraging or even pushing for TSMC capacity in the U.S. — is not about reinforcing a shield around Taiwan. It is about reducing American vulnerability. If conflict were ever to disrupt production in East Asia, Washington wants at least some advanced manufacturing within its own borders. That is industrial risk management, not alliance symbolism.

The Gap Between Symbol and Reality

Yang’s comments highlight a gap between symbolic narratives and operational reality. The Silicon Shield works well as a metaphor, especially in media and policy discussions, but semiconductor supply chains are ultimately governed by physical logistics, capital expenditure, yield learning curves, and geopolitical contingencies.

A fab is not a fortress. It cannot shoot down missiles, nor can it stop political escalation. What it can do is produce chips — and that production can be replicated, over time and at enormous cost, elsewhere. As more advanced capacity gradually appears in the U.S., Japan, and potentially Europe, the idea that Taiwan alone is the irreplaceable node in the system becomes less absolute.

Yang’s point is not that Taiwan’s semiconductor role is unimportant — far from it. Rather, he is warning against over-interpreting economic importance as strategic invincibility. From TSMC’s standpoint, the best defense is not symbolism, but continued leadership in technology, execution, and global integration.

The Two Real Risks to TSMC

Yang makes a striking claim: TSMC effectively has no true industry competitor today. At the most advanced logic nodes, the company’s process maturity, yield performance, customer trust, and ecosystem integration place it in a category of its own. While other manufacturers are pushing forward, none currently match the combination of scale, technology cadence, and operational stability that TSMC delivers at the leading edge.

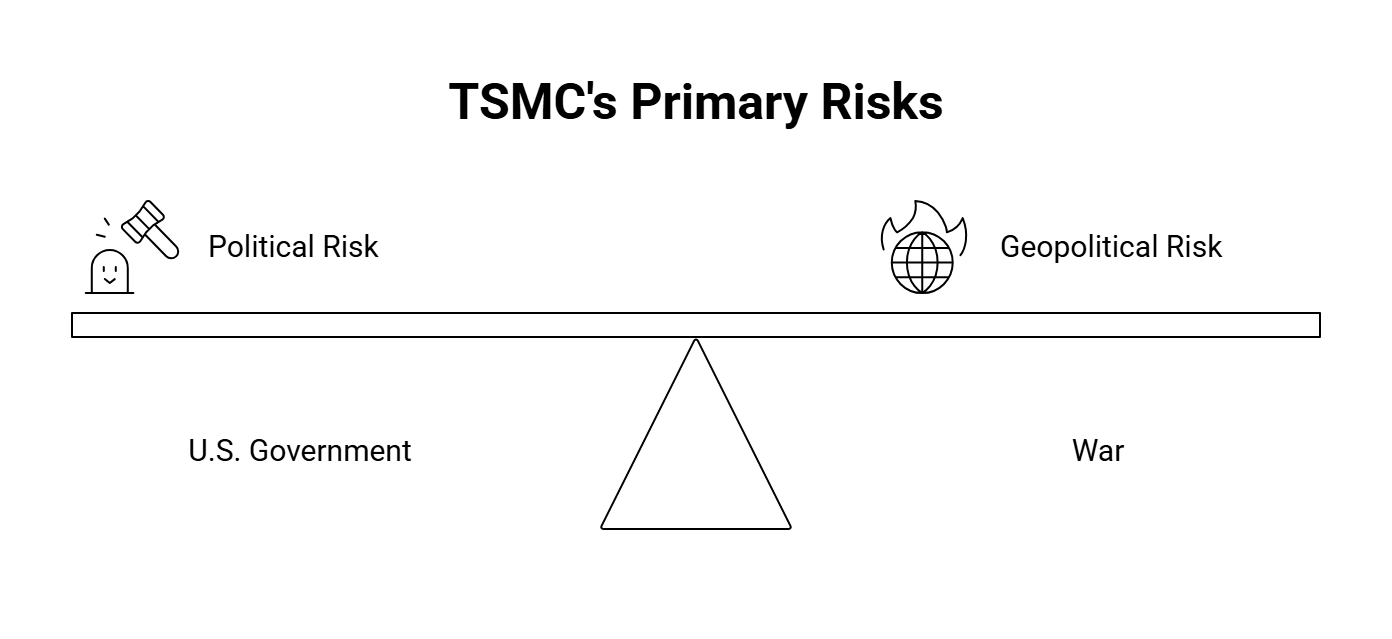

Because of this, Yang argues that the only two real risks facing the company are:

1) The U.S. government

2) War

Not Samsung. Not Intel.

This statement is not meant to dismiss the technological capabilities of other firms, but to underline a shift in the nature of risk. For most companies, the main threats are market-based: price competition, product cycles, customer shifts, or technological disruption. For TSMC, those factors are secondary compared with forces that operate at the state and geopolitical level.

This is what Yang describes as a structural risk, not a market risk. When a company becomes systemically important — comparable to a central bank, a global energy supermajor, or a core telecommunications backbone — its exposure moves beyond normal industry dynamics. Its decisions affect national security, supply-chain resilience, and strategic autonomy. As a result, governments begin to treat the company less as a private enterprise and more as part of critical infrastructure.

In this environment, policy becomes as important as process technology. Regulation, export controls, industrial policy, and geopolitical strategy start to shape the company’s operating space more than commercial rivalry. For example, decisions about where TSMC can build fabs, which customers it can serve, and what technologies it can ship are increasingly influenced by government frameworks rather than purely by market logic.

The U.S. government, in particular, represents a unique kind of risk because it combines regulatory authority, technological leadership, and geopolitical influence. Through export control regimes, subsidy programs, and security-driven industrial policy, Washington can directly affect TSMC’s supply chains, customer base, and geographic footprint. These levers are powerful not because they compete with TSMC, but because they can redefine the rules under which TSMC operates.

The second risk — war — is even more fundamental. Semiconductor fabrication is an ultra-concentrated, capital-intensive activity. A single advanced fab represents tens of billions of dollars in equipment and years of accumulated process learning. Any large-scale military disruption in the region would not simply reduce output; it could halt or destroy the physical base of production. That is a risk no market competitor can match in magnitude.

Taken together, Yang’s argument reframes TSMC’s situation. The company’s dominance at the leading edge shields it from most conventional competitive pressures, but it simultaneously elevates it into a different risk category. TSMC is no longer just competing in an industry — it is operating at the intersection of technology, national strategy, and global power politics.

Why the U.S. Wants TSMC in America

Yang explains that the U.S. push to bring semiconductor manufacturing — including TSMC fabs — onto American soil is not primarily about protecting Taiwan. It is about American risk management.

From Washington’s viewpoint, the semiconductor issue is framed less as alliance symbolism and more as strategic supply security. In a crisis scenario, the core question is brutally practical:

“Can we still get chips?”

Modern military systems, AI infrastructure, cloud computing, telecommunications, and critical industrial equipment all depend on advanced semiconductors. Chips are not just commercial products; they are embedded in defense electronics, satellite systems, encryption hardware, and high-performance computing platforms used for intelligence and simulation. In other words, semiconductors are now a foundational input into national power.

The United States therefore does not view chips as a “shield” that can prevent war by their mere existence in Taiwan. Washington’s strategic community tends to assume that deterrence is built on military posture, alliances, and power balance — not on supply-chain interdependence alone. Economic interdependence can influence decisions, but it is not treated as an absolute barrier to conflict.

Instead, the U.S. approach focuses on resilience. This means redundancy, geographic diversification, and domestic access to key technologies. The logic is similar to energy security: a country that depends on a single foreign source for oil or gas is considered strategically vulnerable. Likewise, a nation that depends on a concentrated overseas location for leading-edge chips faces a systemic risk.

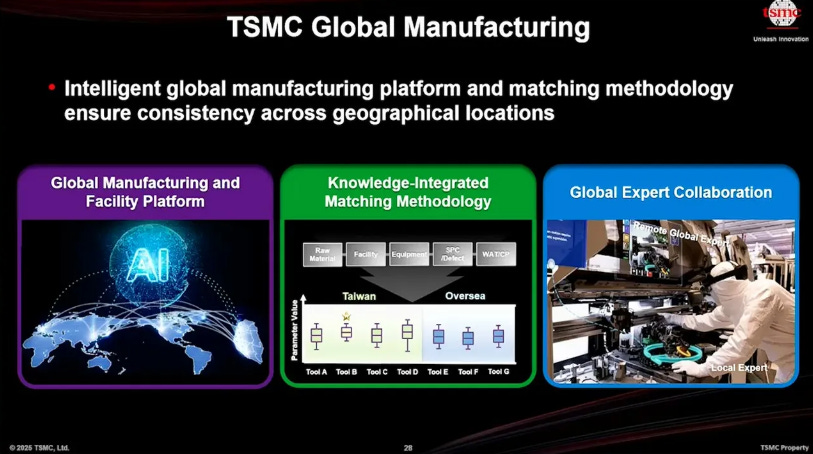

This is why industrial policies such as the CHIPS Act emphasize domestic fabrication capacity, incentives for advanced-node production, and ecosystem development around equipment, materials, and packaging. Encouraging TSMC to build in the United States is part of this broader effort. The goal is not to replace Taiwan overnight — that would be unrealistic — but to ensure that at least some critical capacity exists within U.S. borders.

From this perspective, bringing TSMC to America is an act of risk hedging. It creates a backup node in the global manufacturing network. Even if that node initially operates at higher cost or smaller scale, its value lies in strategic insurance rather than short-term economic efficiency.

However, Yang points out that this very process changes the meaning of the Silicon Shield. If advanced production is no longer overwhelmingly concentrated in Taiwan, then Taiwan’s unique leverage derived from semiconductor centrality becomes less absolute. The “shield” becomes thinner, not because Taiwan’s industry is weaker, but because the system is being deliberately rebalanced.

In short, U.S. policy is driven by the desire to reduce its own vulnerability, not to reinforce a symbolic deterrent centered on Taiwan. This is a shift from interdependence as protection toward resilience as security — and it reshapes the geopolitical role of TSMC in the process.

A Shield That Is Getting Thinner

Yang acknowledges that Taiwan’s reliance on the Silicon Shield has become less effective over time. In the early days of the concept, Taiwan’s dominance in advanced semiconductor manufacturing appeared almost absolute. The most cutting-edge logic production, the densest ecosystem of suppliers, and the most experienced engineering base were overwhelmingly concentrated on the island. Under those conditions, the idea that Taiwan uniquely “held the key” to the world’s digital infrastructure felt convincing.

But the semiconductor landscape is not static. As production globalizes — with new fabs being built in the United States, Japan, and potentially Europe — the concentration risk that once defined the system is gradually being redistributed. Even if Taiwan remains the largest and most advanced hub, the relative exclusivity of its position is decreasing. The global supply chain is evolving from a single critical node toward a more distributed network.

In this sense, the Silicon Shield is not disappearing, but it is becoming thinner. Its power as a singular point of leverage weakens as redundancy increases. For policymakers, redundancy is a positive outcome because it reduces systemic vulnerability. For Taiwan, however, it also means that semiconductor centrality alone cannot carry the full weight of national security expectations.

Yang emphasizes that the United States still has substantial strategic reasons to care about Taiwan beyond semiconductors. Taiwan’s location in the first island chain, its role in regional alliances, and its place in the broader Indo-Pacific balance of power all matter independently of chip production. These factors anchor Taiwan within a wider strategic framework that does not rise or fall solely on the semiconductor industry.

The danger, in Yang’s view, lies in treating semiconductor dependency as a single-source guarantee of protection. Security is multi-layered — built from military posture, diplomacy, economic resilience, and societal strength. Chips can be part of that picture, but they cannot substitute for it. Over-reliance on the Silicon Shield risks creating a false sense of certainty in a world where technological and geopolitical realities are continuously shifting.

Taiwan’s “Comfort Trap”

Yang goes further, offering not just a geopolitical or industrial argument, but a cultural critique.

He cites a line from the Song Dynasty scholar Su Dongpo:

“The people’s greatest danger is knowing comfort but not danger; being able to enjoy ease but unable to endure hardship.”

In Yang’s view, this warning resonates strongly with Taiwan’s current situation. Decades of economic success, political stability, and technological achievement have created an environment of relative comfort. Living standards have risen, global integration has deepened, and the semiconductor industry has become a source of national pride. Yet that very success can also create a psychological risk: the gradual assumption that the existing order will continue automatically, without the need for continuous effort, resilience, and adaptation.

Yang argues that Taiwan has grown too comfortable and too dependent on government-centered solutions. When problems arise — whether economic, social, or strategic — there is often an expectation that policy alone can solve them. This mindset, he suggests, weakens society’s ability to prepare for uncertainty and hardship. In this sense, the issue is not just about defense or diplomacy, but about collective mentality.

He also stresses that Taiwan’s semiconductor rise was not the outcome of a master plan to create a “shield.” It was the product of a rare convergence of timing, talent, institutional learning, and global market opportunity. The industry emerged from decades of engineering accumulation, ecosystem building, and integration into international supply chains — not from a deliberate strategy to turn chips into geopolitical leverage.

Over-reliance on the Silicon Shield, in Yang’s view, reflects a deeper societal habit of expecting protection from outside forces — whether from technology, from major powers, or from abstract strategic concepts. This can lead to a form of strategic complacency, where economic strength is mistaken for automatic security.

A similar idea appears in Western thought. U.S. President John F. Kennedy once remarked, “The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining.”

The message is the same: periods of stability and prosperity are precisely when preparation and strengthening should occur, not relaxation. Comfort is not an endpoint but a window of opportunity to build resilience.

Yang’s broader point is that national strength ultimately depends on society’s capacity to endure pressure, adapt, and act with discipline — not merely on possessing a globally important industry. Semiconductors can be an asset, but they cannot replace the need for self-reliance, civic responsibility, and long-term strategic awareness.

From Carrier to System Platform

Yang’s message, in the end, is less about fabs and geopolitics than about mindset. Semiconductors should be understood as an extraordinary economic strength — a pillar of Taiwan’s global relevance and technological capability — but not as a magical guarantee of safety. Treating the industry as a protective charm risks confusing influence with immunity.

In engineering terms, Yang is calling for a shift similar to what has happened inside advanced packaging. A substrate was once just a carrier — a passive base holding components together. Today, it has evolved into a system platform, integrating power delivery, signal routing, and thermal management into the structure itself. Security, Yang suggests, must evolve in the same way: from a single supporting element to a multi-layered, system-level architecture.

National resilience cannot rest on one industry, no matter how advanced. It must be built across industrial capability, technological depth, educational quality, social cohesion, and civic responsibility. Economic strength provides resources, but societal strength provides endurance. Innovation creates growth, but discipline and preparedness create stability.

In this framework, semiconductors are part of the system — important, even critical — but not the whole structure. True security resembles a diversified engineering design: multiple redundancies, balanced loads, and the ability to withstand shocks without catastrophic failure.

Yang summarizes his philosophy with a simple but demanding idea:

“Only by standing on your own can you help others stand.”

The statement reflects a belief that self-reliance is not isolationism, but the foundation of meaningful partnership. A society that cultivates internal strength — economic, intellectual, and moral — is better positioned to contribute to alliances and global cooperation. Dependence invites anxiety; capability invites confidence.

For Taiwan, the path forward, in Yang’s view, is not to abandon semiconductors, nor to deny their importance, but to place them in proper proportion. Chips can power the digital world, but resilience must power the nation.

#下班國際線 台積電不想當護國神山?拯救台灣不靠矽盾!楊光磊直言:台灣人不當「媽寶」才有救! ft.楊光磊|2026-01-31 Ep.35| 路怡珍

This article is based on watching an interview with Yang Kuang-Lei and incorporates analysis and perspectives from SemiVision.