15-Minute Deep Dive into the Data Center Cooling Revolution: From Chillers to Liquid Cooling

Original Article bBy SemiVision Research (NVIDIA, TSMC, AVC, Foxconn)

Industry Background and Trends: Cooling Innovation Driven by the High-Power AI Era

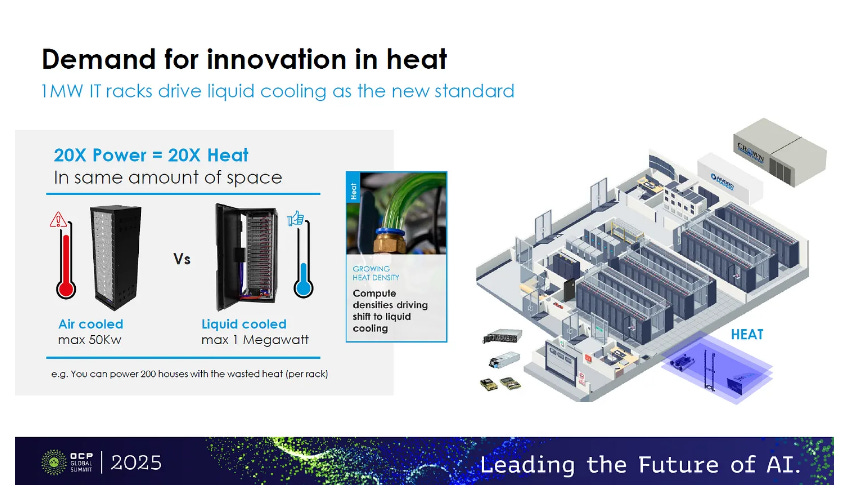

The rapid rise of AI servers and high-performance computing (HPC) has pushed data center cooling requirements to an unprecedented level. The latest generation of AI chips—such as NVIDIA’s H100 and Grace Hopper—now carry thermal design power (TDP) ratings that often reach several kilowatts, far beyond what traditional air-cooling systems can effectively handle. For example, NVIDIA’s GB200 and GB300 chips feature TDPs ranging from 1,200W to 2,700W, significantly exceeding the roughly 700W practical limit of air cooling. As heat density continues to increase at an exponential pace, server cooling methods based primarily on fan-driven air convection are steadily approaching their physical limits. In short, high-power AI chips are triggering a new wave of cooling transformation in data centers, making conventional air-cooling architectures unsustainable and positioning liquid cooling as an inevitable solution for high-power servers.

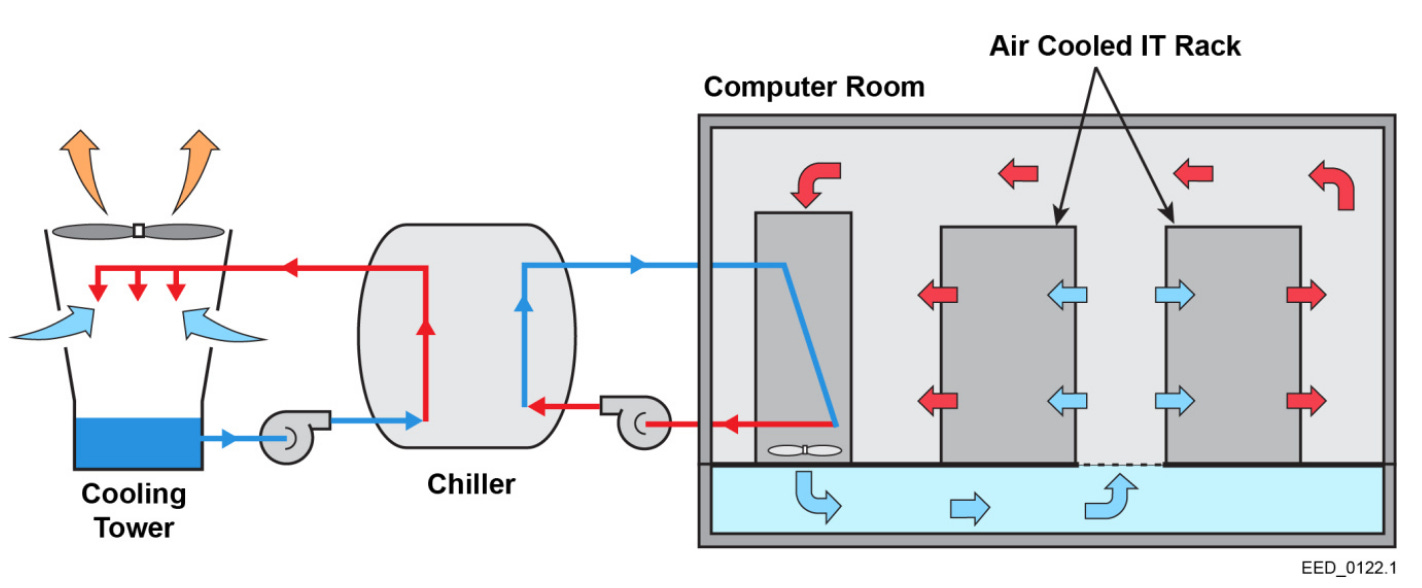

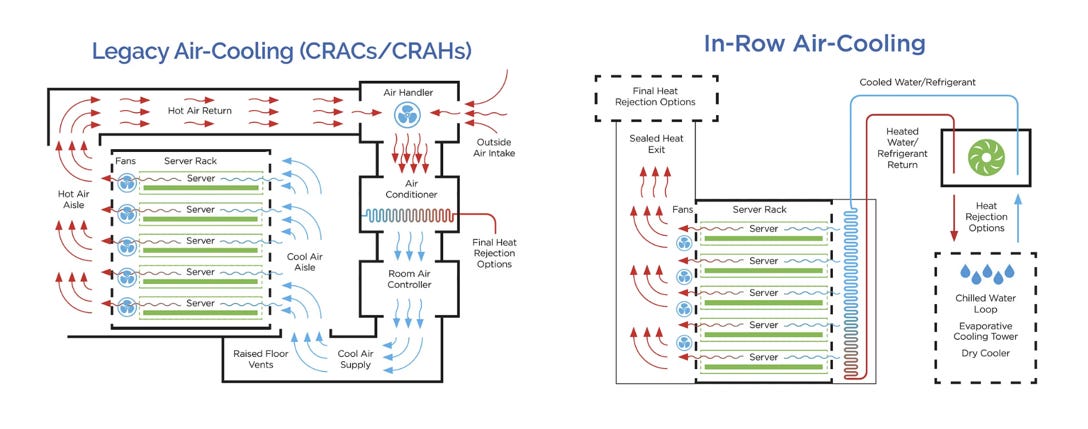

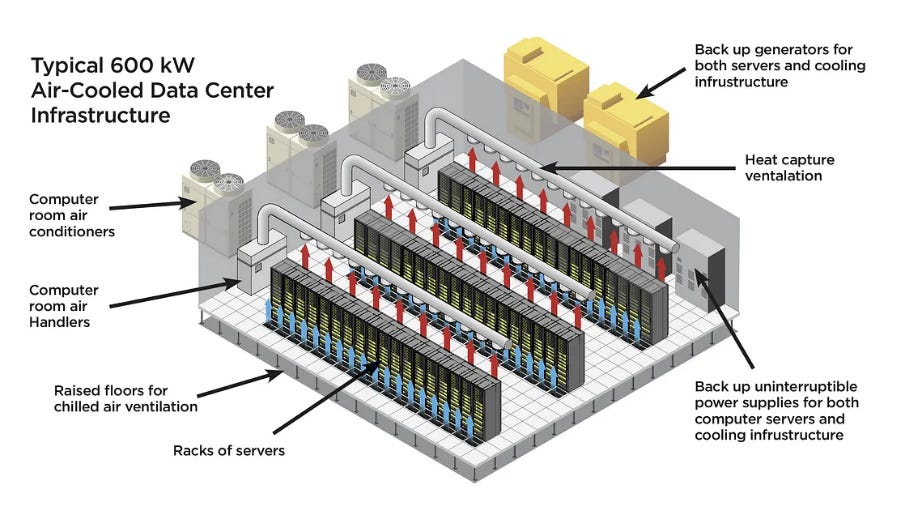

At the same time, growing pressure from overall energy consumption and carbon emissions is forcing data centers to rethink their cooling strategies. Traditional data centers have long relied on chillers combined with CRAC (Computer Room Air Conditioning) systems, lowering chilled water temperatures to around 7–12 °C to cool server room air. However, chillers essentially function like massive air-conditioning compressors with extremely high power consumption. They are not only among the largest energy consumers in a data center, but also a major reason why PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) is difficult to reduce. Conventional chiller-based data centers typically operate at a PUE of around 1.5–2.0, indicating that a substantial portion of electricity is consumed by cooling infrastructure rather than IT equipment itself. Under the dual pressures of global carbon-neutrality targets and rising operating costs, reducing cooling-related energy consumption has become an industry-wide consensus. As a result, next-generation data centers are increasingly experimenting with eliminating chillers altogether, instead adopting higher-temperature cooling water in combination with liquid-cooling technologies to achieve significant efficiency gains.

Conventional chiller-based cooling architectures commonly used in traditional data centers

Chillers rely on compressor-driven refrigeration cycles to forcibly lower water temperatures, after which air-conditioning systems distribute cooled air throughout the server rooms to remove heat. Under this architecture, cooling systems often become the second-largest power consumer after IT equipment, keeping overall energy consumption persistently high.

In contrast, liquid-cooled data centers can eliminate traditional chillers altogether and instead adopt a dual-loop liquid cooling architecture. In this design, an internal coolant loop directly removes heat from server components and transfers it via in-rack or row-level Cooling Distribution Units (CDUs) to an external loop, where the heat is dissipated through outdoor cooling towers or dry coolers. Because liquid cooling systems allow server outlet water temperatures to reach approximately 45 °C—or even higher—well above ambient temperatures in most regions, they enable free cooling, leveraging ambient air to dissipate heat without relying on energy-intensive compression-based refrigeration equipment.

This high-temperature liquid cooling paradigm was described by NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang at this year’s CES as a revolutionary shift toward “cooling servers with warm water”. Huang noted that, going forward, 45 °C warm water will be sufficient to cool chips operating above 80 °C, eliminating the need for chillers and effectively enabling supercomputer-scale cooling using warm water. These remarks initially led to market misinterpretation that “cooling demand would disappear,” triggering short-term sell-offs in liquid cooling-related stocks. In reality, the opposite is true: removing chillers does not reduce cooling demand—it represents a structural transition toward liquid-centric cooling architectures.

With the exit of compression-based refrigeration equipment, the thermal load previously handled by chillers is now fully absorbed and transported by liquid cooling systems. As a result, the volume, importance, and strategic value of liquid cooling infrastructure continue to rise rather than decline.

Overall, the dual forces of AI-driven compute density and energy efficiency imperatives are accelerating the adoption of liquid cooling across data centers. Hyperscale cloud providers such as AWS, Google, and Meta have already begun deploying in-house AI chips alongside purpose-built liquid cooling infrastructure to increase compute density while reducing energy consumption. Industry analysts estimate that liquid cooling penetration in AI data centers will reach 33% by 2025 and rapidly become the dominant mainstream solution by 2026.

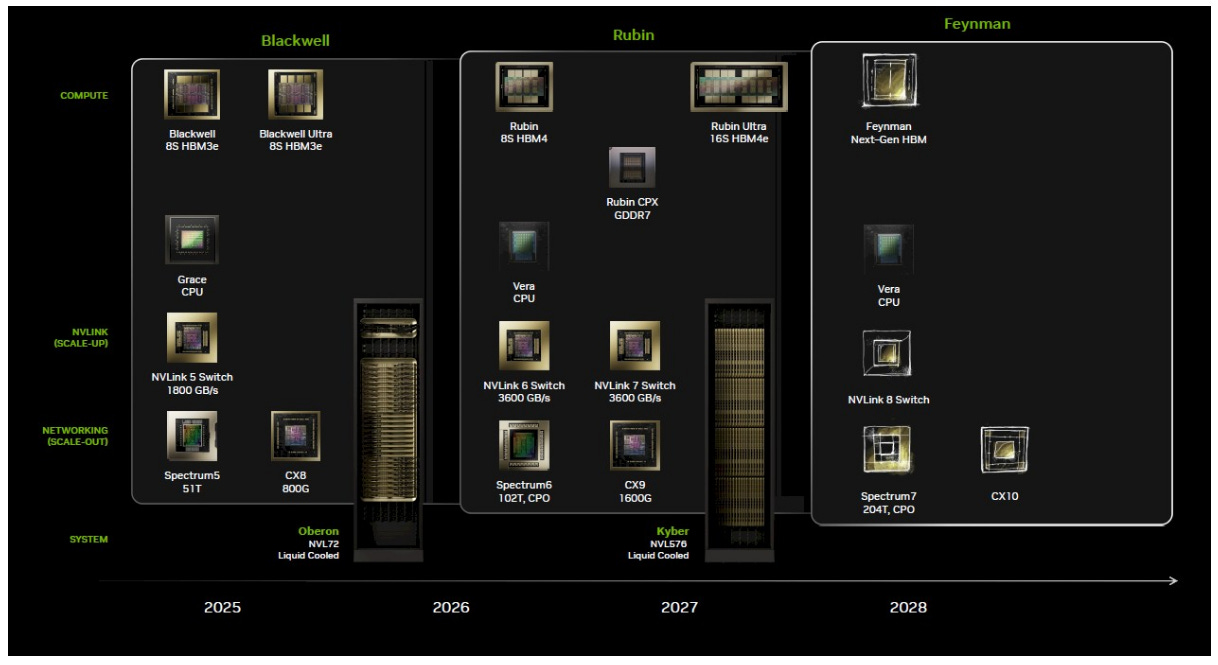

Looking ahead, as single-rack IT loads routinely exceed 100–200 kW—such as NVIDIA’s latest Vera Rubin racks, which surpass 200 kW in thermal output—liquid cooling systems have become indispensable core infrastructure rather than optional enhancements. Even more striking is the impact on energy efficiency: with chillers removed, next-generation liquid-cooled data centers could reduce PUE from over 1.5 in traditional air-cooled facilities to around 1.1, potentially approaching 1.05 or even as low as 1.02 under highly optimized conditions. At that point, power consumption is largely limited to circulation pumps and a minimal number of auxiliary fans.

This represents a dramatic leap in energy efficiency and carbon emission reduction, aligning closely with long-term sustainability goals. It also reinforces a critical conclusion: cooling demand is not declining—it is increasing. What is changing is the method, shifting from power-hungry air conditioning systems to highly efficient liquid cooling architectures. The industry is now entering an era of high-efficiency computing dominated by warm-water liquid cooling.

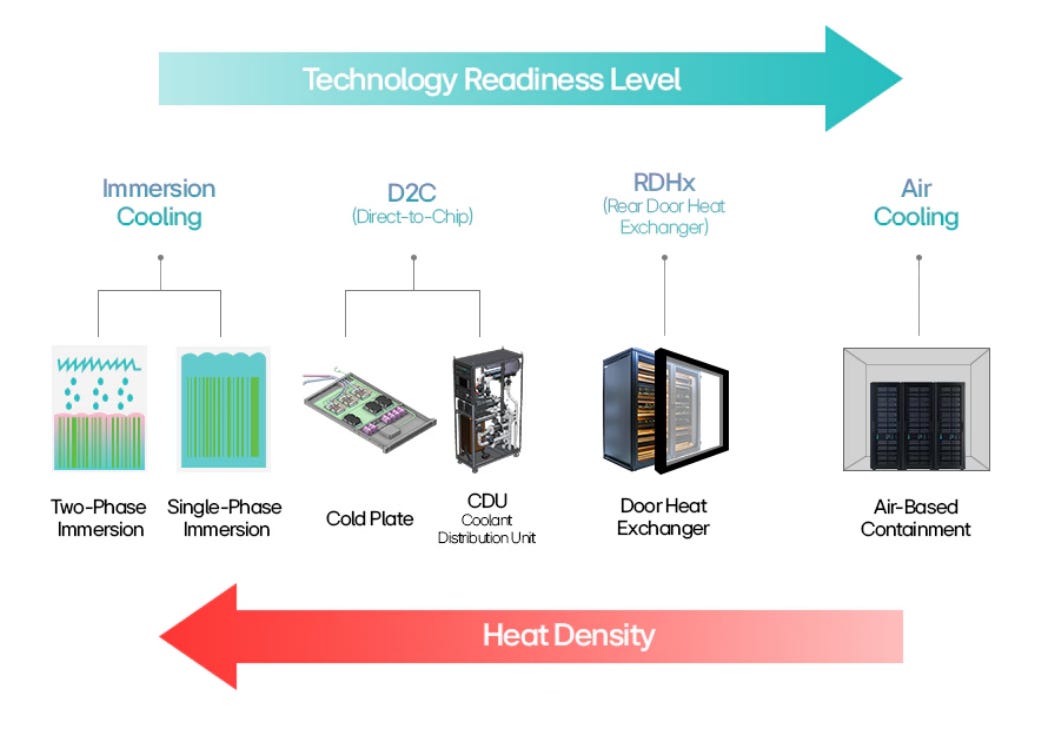

Technology Roadmap: Comparing Air Cooling, Chiller-Based Systems, and Liquid Cooling Solutions

Data center cooling technologies are undergoing a generational transition. From a technology roadmap perspective, we compare traditional air cooling (including chiller-based systems) with the two primary liquid cooling approaches—immersion cooling and direct-to-chip cold plate liquid cooling—analyzing their respective advantages, limitations, applicable scenarios, technical bottlenecks, and future investment trajectories.

Below are some of the articles related to thermal management and cooling that we have previously published at SemiVision.

Readers who are interested are welcome to click through and explore them at their own pace.

TSMC x Nvidia : Breaking the Thermal Wall: How Advanced Cooling Is Powering the Future of Computing

Looking ahead to 2026, SemiVision will launch a new suite of enterprise-level customized services designed for Business Development and Market Intelligence teams. These project-based services deliver decision-grade insights — not just information — helping companies navigate rapid shifts in the semiconductor industry, from technology node evolution and supply-chain restructuring to competitive dynamics and emerging opportunities.

Our focus areas include advanced packaging (CoWoS, CoPoS, SoIC, CPO), silicon photonics and Optical I/O, AI and HPC system architecture, bottleneck migration in key materials and equipment, and the real impact of geopolitics on capacity and supply chains. Through cross-technology and cross-value-chain analysis, we help teams identify inflection-point technologies, rising or displaced supplier roles, and translate complex industry changes into actionable strategy.

Service formats include custom research projects, technology and supply-chain mapping, roadmap comparisons, partnership or investment assessments, and executive-level briefings and training. SemiVision’s role is to bridge technical understanding with market judgment — enabling companies to understand not only what is happening, but why, and how to position accordingly.

For deeper industry analysis or customized discussions, contact:

jett@semivisiontw.com | eddyt@semivisiontw.com

SemiVision Tech Insight Report Outline

From Thermal Bottlenecks to System-Level Cooling Architecture

Foundations of Thermal Architecture in AI Systems

Evolution of TIM Materials

Advanced Packaging Thermal Roadmap

Liquid Cooling Architecture Evolution

Thermal Materials Supply Chain

Taiwan supply chain in the AI Thermal Supply Chain

TSMC Thermal Solution

Traditional Air Cooling (Including Chiller-Based Systems)

Architecture and Characteristics

Traditional air cooling has been the dominant data center cooling architecture for decades. It primarily relies on server fans to exhaust hot air, while Computer Room Air Conditioning (CRAC) systems—paired with chillers—cool the surrounding environment. In simple terms, cold air flows through servers to remove heat.

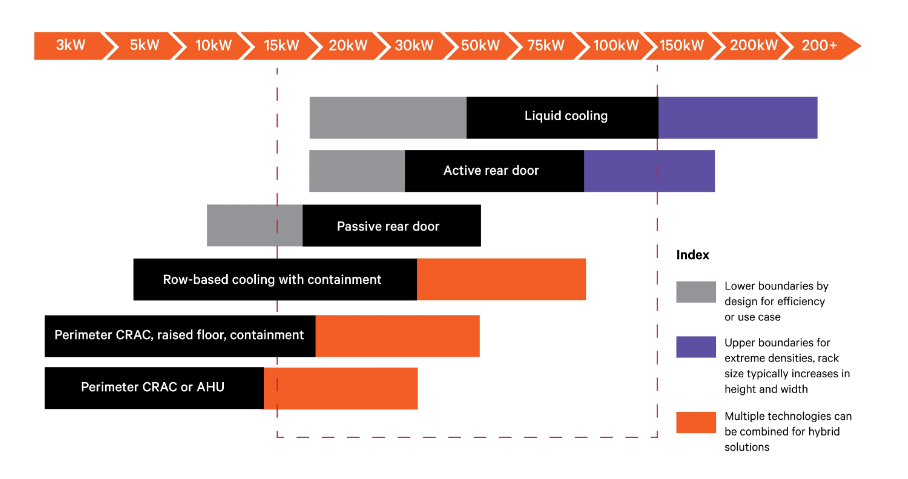

Large-scale data centers typically deploy chillers to supply chilled water at 7–12 °C to air-handling units, maintaining server inlet temperatures within acceptable ranges (such as OCP-defined W17 or W27 classes). The advantages of this architecture include technical maturity, widespread familiarity among facility and operations personnel, and minimal modification required at the server level. For low-to-moderate power-density racks, air cooling remains cost-effective and relatively easy to maintain, as replacing fans or air-conditioning modules is straightforward.

Limitations and Bottlenecks

Air cooling performance is fundamentally constrained by the low heat capacity and thermal conductivity of air. As chip power density continues to rise, air becomes increasingly incapable of removing sufficient heat—especially when individual server nodes exceed kilowatt-level power consumption. Moreover, because air cooling depends on lowering the temperature of the entire data hall, increasing IT load requires disproportionate increases in air-conditioning capacity, driving up energy consumption and PUE. Chillers themselves are highly energy-intensive, pushing traditional architectures close to their efficiency ceiling.

Studies indicate that air cooling reaches its practical limit at around 700 W per chip TDP; beyond that point, adding more fans yields diminishing returns. As a result, air cooling alone is insufficient for today’s AI clusters that routinely operate at hundreds of kilowatts per rack. The core bottleneck is twofold: physical limits that cannot be overcome, and escalating economic and environmental costs if cooling relies solely on higher air-conditioning power.

Application Scenarios and Trends

Traditional air cooling remains suitable for general enterprise data centers, low-to-medium density IT environments, and scenarios highly sensitive to upfront capital expenditure. However, as AI and high-density computing proliferate, air cooling is steadily losing share to liquid cooling solutions. Many newly built hyperscale data centers now pre-install liquid cooling piping or adopt liquid-ready designs to extend infrastructure lifespan.

Overall, air cooling is at a strategic inflection point—transitioning from a primary solution to a secondary one. In the future, it will likely be reserved for auxiliary, low-power equipment, while high-power compute workloads are increasingly handed over to liquid cooling.

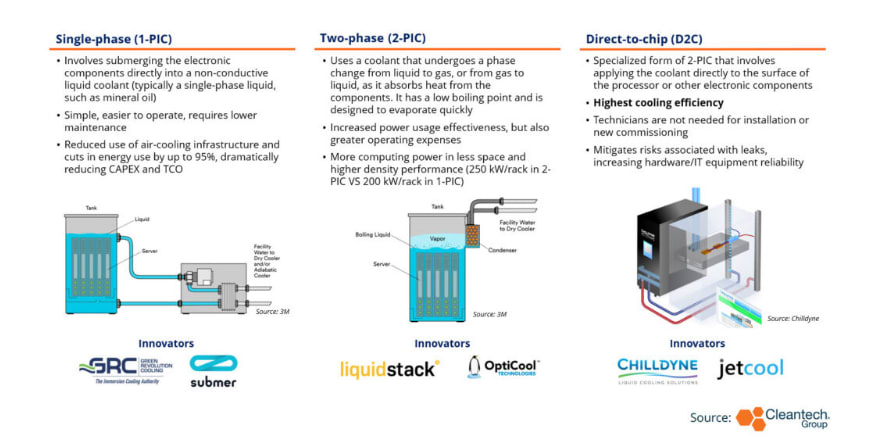

Immersion Cooling

Architecture and Characteristics

Immersion cooling removes heat by submerging entire servers—or electronic components—directly into specialized dielectric fluids. These fluids may be single-phase (e.g., mineral oils or fluorinated liquids) or two-phase liquids that boil and condense. From a thermal perspective, liquids possess far higher heat capacity than air, enabling much more effective heat absorption.

A key advantage of immersion cooling is uniform thermal management: not only CPUs and GPUs, but also power supplies, memory modules, and VRMs are fully immersed and cooled. This makes immersion particularly suitable for ultra-high power-density environments. Additionally, server fans can be eliminated, reducing noise and some power consumption. From a facility standpoint, immersion systems also reduce the need for air ducts and wide rack spacing, improving space utilization.

Limitations and Bottlenecks

Despite its technical appeal, immersion cooling faces significant deployment and operational challenges. First, dielectric fluids are expensive and require ongoing maintenance; long-term issues such as oxidation, evaporation, and fluid degradation must be managed. Second, server vendors have concerns about component reliability in immersion environments—certain rubber, plastic, or connector materials may degrade over time, and warranty responsibilities remain unclear.

Maintenance complexity is another barrier. Unlike conventional servers that can be easily slid out of racks, immersion systems require lifting servers from fluid baths, managing dripping fluids, and adhering to strict operational procedures—introducing a steep learning curve for operations teams. Finally, the industry lacks standardized immersion specifications; tank dimensions and system designs vary widely, limiting scalability. These factors collectively constrain near-term adoption.

Application Scenarios and Trends

Immersion cooling is currently deployed primarily in niche or pilot-scale applications. Examples include high-frequency trading, military and aerospace electronics, and early cryptocurrency mining clusters seeking extreme cooling efficiency. Some hyperscalers have conducted proof-of-concept trials—Microsoft, for example, tested two-phase immersion to evaluate efficiency and component longevity. Certain edge computing deployments or harsh-climate environments also consider immersion cooling.

Overall, immersion cooling remains a non-mainstream option, serving as a complementary technology within the broader liquid cooling landscape. Broader adoption may occur if power densities exceed the capabilities of cold plate solutions or if standards and ecosystems mature. However, in the 2025–2026 investment horizon, industry focus remains firmly on cold plate liquid cooling due to its superior integrability.

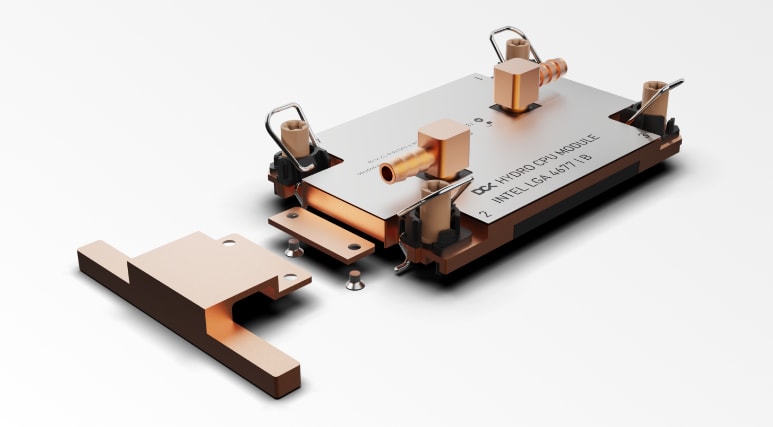

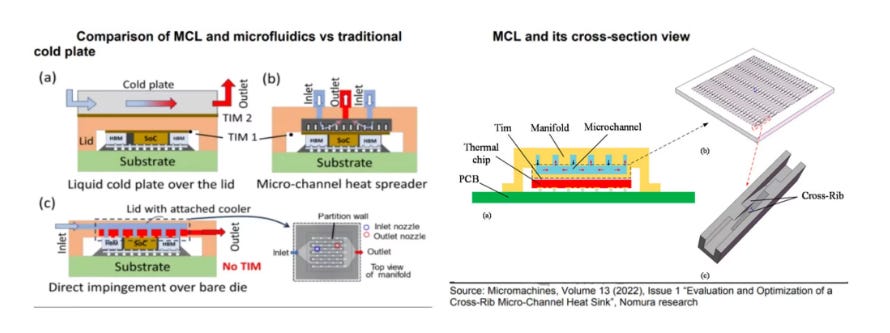

Direct-to-Chip Cold Plate Liquid Cooling

Architecture and Characteristics

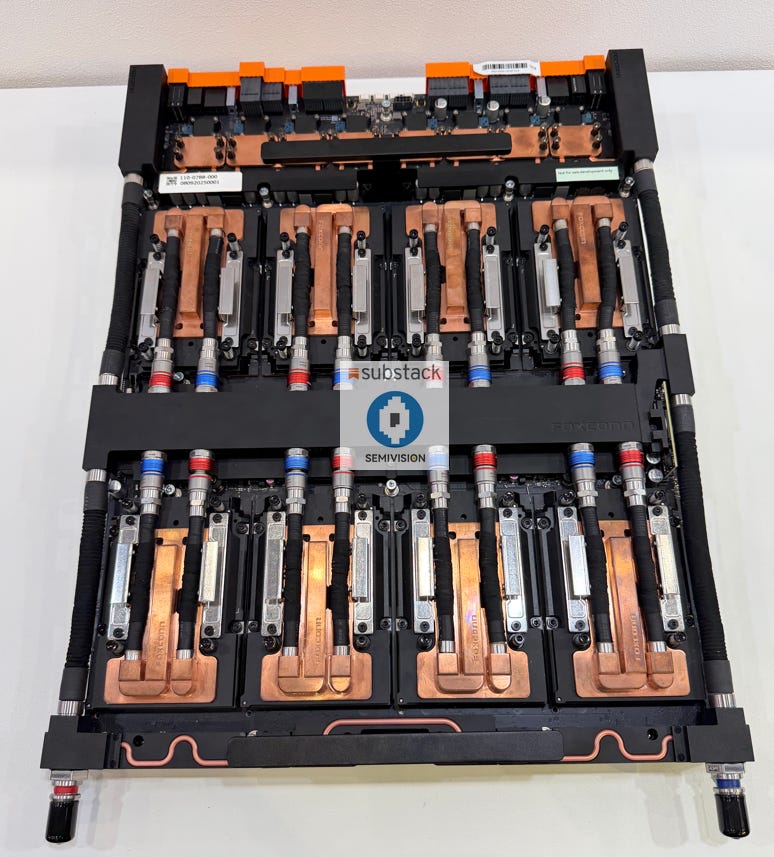

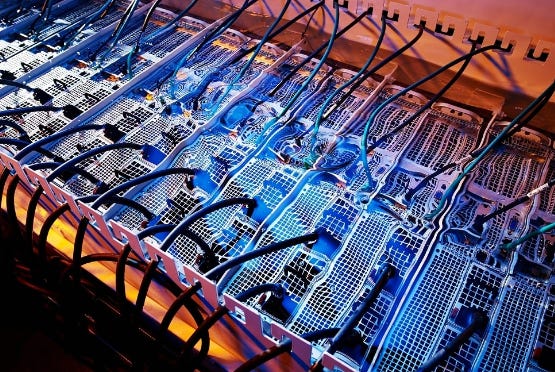

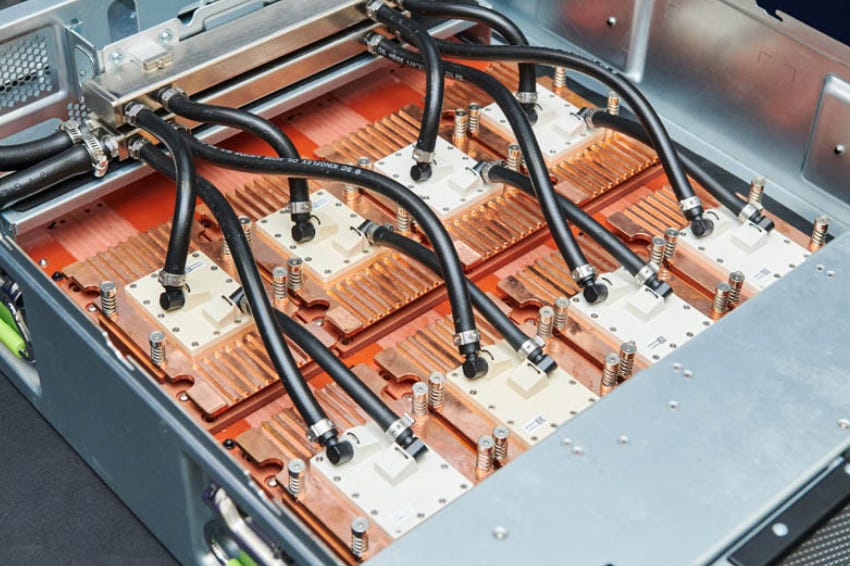

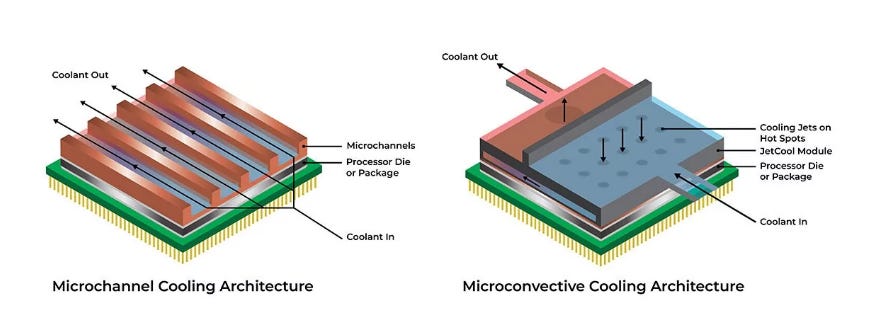

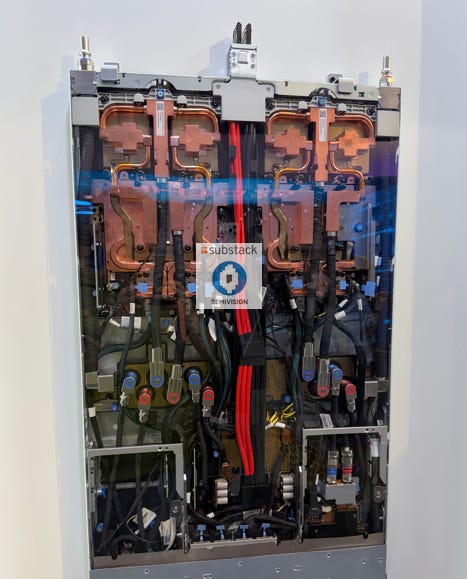

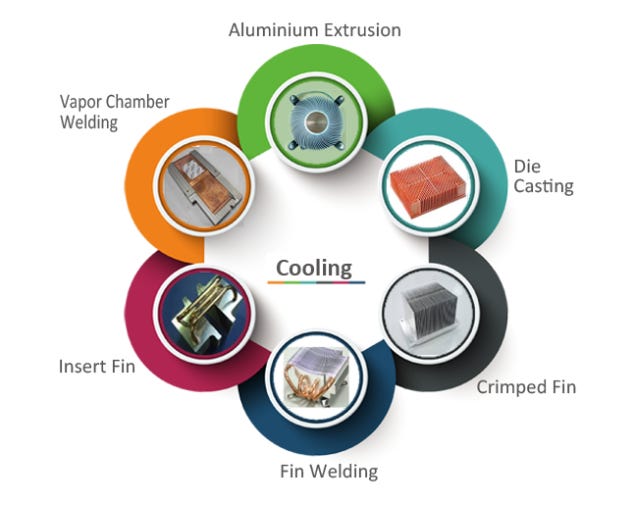

Cold plate liquid cooling is currently the dominant liquid cooling solution in data centers. It involves mounting cold plates directly onto high-heat components such as CPUs and GPUs, allowing coolant to flow through internal microchannels and remove heat at the source. Each major component is typically covered by a custom-designed cold plate, with manifolds and quick-disconnect (QD) couplings distributing and collecting coolant.

Server racks are usually equipped with one or more Cooling Distribution Units (CDUs), which act as thermal exchange and control hubs. CDUs connect internal hot-water loops to external facility water loops, transferring heat via plate heat exchangers while managing flow and temperature.

The performance advantage is substantial: liquid cooling directly targets chip heat sources and is orders of magnitude more efficient than air convection, maintaining lower operating temperatures and ensuring stable performance. Cold plate systems also support higher coolant temperatures (30–45 °C), enabling free cooling in most climates and eliminating the need for chillers. Architecturally, cold plate cooling preserves rack-based server form factors, enabling smoother adoption and hybrid deployments in existing data centers.

Limitations and Bottlenecks

Despite its maturity, cold plate liquid cooling faces several technical challenges. Leak risk management is paramount: numerous QD couplings and hoses increase the probability of coolant leakage, which can damage equipment and cause downtime. As a result, suppliers invest heavily in high-reliability connectors, leak detection, and protection mechanisms.

Manufacturing complexity is another bottleneck. Next-generation cold plates increasingly adopt microchannel designs to improve heat transfer. NVIDIA’s upcoming Vera Rubin systems, for example, incorporate MCCP (Micro Channel Cold Plates) for primary AI chip cooling. These advanced designs raise manufacturing difficulty, cost, yield risk, and capacity constraints.

Customization requirements also increase development effort, as each new chip generation features different sizes and heat profiles, necessitating close collaboration with chip designers. Initial deployment costs are significantly higher than air cooling due to additional piping, pumps, and CDUs, requiring scale to amortize investments. Operationally, liquid cooling introduces new maintenance skills and training requirements.

Application Scenarios and Trends

Cold plate liquid cooling has become the mainstream choice for AI training servers and supercomputing centers. NVIDIA’s latest HGX/H100 servers and future Vera Rubin platforms are fully liquid-cooled, often eliminating internal fans entirely. Next-generation racks—such as NVIDIA’s announced “Kyber” architecture—will further increase liquid cooling density and component integration .

Hyperscale cloud providers are also extending liquid cooling beyond GPUs to custom AI ASICs. AWS’s upcoming Trainium 3, Google’s TPU v6, and Meta’s MTIA 2 are all expected to adopt liquid cooling for stability and density reasons, even when per-chip TDP remains below 1,000 W. Liquid cooling is thus rapidly permeating both GPU and ASIC ecosystems.

Looking ahead to 2027, NVIDIA is reportedly planning to introduce chip-level liquid cooling solutions such as Micro Channel Lids (MCL) to address potential chip TDPs exceeding 3,000 W. MCL integrates microchannel cooling directly into the package lid, shortening thermal paths and further improving efficiency. While still in R&D and pilot production, this approach could significantly reshape system design and component ecosystems if successfully commercialized.

Overall, cold plate liquid cooling investment will accelerate in tandem with AI compute growth. The period from 2024 to 2026 represents a critical expansion phase, followed by continued iteration driven by advanced technologies such as MCL and two-phase cold plates—marking an ongoing evolution toward ever-higher thermal efficiency.

Taking all segments together, the penetration of liquid cooling is creating structural growth opportunities across the supply chain. In particular, vendors that possess capabilities in cold plates, quick disconnects (QDs), CDUs, and system-level design integration are expected to achieve growth rates well above the broader technology sector average over the next several years.

For example, AVC is expected to deliver revenue growth of over 30% in 2026, driven primarily by existing GB300 orders, the ramp-up of thermal modules for NVIDIA’s new Vera Rubin platform, and the expansion of its chassis and rack-level integration offerings.

Impact of Chiller Removal on Market Size

A key question is whether the removal of chillers will shrink or fundamentally alter the overall data center cooling market. As discussed above, although chillers are being phased out, this does not imply a reduction in total cooling demand. Instead, value is shifting from centralized, large-scale refrigeration equipment toward a distributed ecosystem of high-precision liquid-cooling components.

Traditional chiller systems carry high capital costs and energy consumption. While eliminating chillers allows data centers to reduce spending on large HVAC infrastructure, a substantial portion of this budget is reallocated to liquid-cooling systems—including a greater number of cold plates, significantly higher volumes of connectors and piping, more complex CDU modules, and comprehensive monitoring and maintenance solutions. NVIDIA’s assertion that future data centers “no longer need chillers” reflects a fundamental shift in heat-exchange logic, not the elimination of cooling hardware itself. Once compression-based refrigeration is removed, the cooling function previously handled by chillers is directly assumed by the liquid-cooling system.

As a result, the overall usage and strategic importance of liquid cooling increase in tandem, while commercial opportunities migrate from traditional HVAC manufacturers to next-generation liquid-cooling suppliers. In practice, beginning in 2026, high-end racks deployed by hyperscale cloud providers will be almost entirely liquid-cooled. Both the total market size and per-rack thermal value are rising simultaneously. Estimates suggest that the global liquid-cooling market will enter an explosive growth phase by 2026, with cold plate revenue growing at over 55% year-on-year, while per-rack thermal component value—driven by higher usage of quick disconnects and related parts—will increase by more than 50%.

This means that even without traditional chiller sales, the incremental value generated by liquid-cooling equipment is sufficient to offset and surpass the gap, allowing the overall cooling industry to continue expanding. For players across the value chain, the ability to capture new opportunities—from component manufacturing to system-level integration—will be decisive in shaping their long-term competitive positioning.

In summary, the exit of chillers has not weakened cooling demand. Instead, it marks the formal arrival of the high-temperature liquid-cooling era. Cooling solution suppliers that successfully scale R&D investment and vertical integration stand to gain significantly from this structural transformation in data center cooling technology.

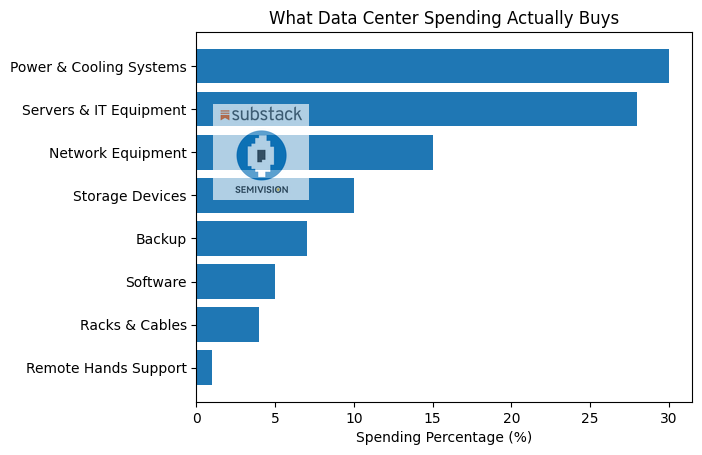

What Companies Are Really Buying When They Build a Data Center

Building a fully equipped data center is far more than a simple construction project—it is a highly structured capital allocation exercise across multiple technical systems that together ensure performance, uptime, and scalability.

In the United States, constructing and fitting out a modern data center in 2025 typically costs $600–$1,100 per square foot, with high-end AI facilities exceeding standard budgets. Large-scale facilities can range from $250 million to over $500 million, while smaller enterprise deployments may be completed for $2–5 million.

When breaking down the bill of materials (BOM) for a representative ~$10 million data center build, spending is distributed as follows:

The largest portion—30%—goes to power and cooling systems. These systems are fundamental to maintaining operational stability and include electrical infrastructure, UPS systems, chillers, and thermal management. As compute density rises, especially in AI workloads, this category continues to grow in importance.

Servers and IT equipment account for 28% of total costs. This category forms the computational core of the facility, covering processing hardware and related components that deliver actual workload performance.

Network equipment represents 15% of spending. These systems connect servers within the data center and link the facility to external networks. As data flows intensify and latency requirements tighten, networking becomes increasingly critical.

Storage devices make up 10% of the budget, supporting data retention, retrieval, and management across primary and secondary tiers.

Backup and disaster recovery solutions account for 7%, ensuring resilience and business continuity in the event of failures.

Software comprises 5% of total investment, enabling data center management, monitoring, orchestration, and optimization of resources.

Physical infrastructure is still necessary but represents a smaller share: racks and cabling take 4%, while remote hands support services account for just 1%.

What stands out is that data centers are not primarily IT purchases—they are infrastructure systems engineered to sustain high-density computation. Nearly one-third of spending goes to energy and thermal management, highlighting a key reality of the AI era:

The bottleneck is no longer just compute performance—it is power delivery and heat removal.

Understanding this cost structure is essential for investors, operators, and supply chain participants seeking to identify where value and constraints truly lie in next-generation data infrastructure.